On a climate-change-driven balmy evening last September, I attended a launch party for C Magazine on the patio of that Toronto club with the Canadiana name: the Beaver. Performing a quick count, I calculated that about half of the attendees didn’t live in Canada permanently: they either lived in Berlin or LA, full-time or part-time. I had just returned from Brazil; a friend at the launch was on her way there.

It didn’t use to be like this–say, 20 years ago.

A few artists moved to New York, usually after

receiving a grant; Canada Council award recipients

stayed as they do now in the Paris studio;

and a few others, like Vincent Trasov and

Michael Morris, who both moved to Berlin in

the early 80s, settled in other European cities.

Nevertheless, the new mobility does follow

a Canadian tradition in the visual arts: leaving

the country. In 1890, for instance, post-Impressionist

JW Morrice moved to Europe

from Montreal and after a brief sojourn for

study in London, England, he relocated

permanently to France, beginning with Paris,

where he became the model for the Somerset

Maugham character Cronshaw, the alcoholic

poet in Of Human Bondage (1915). Morrice’s

increasingly frequent exhibitions received

laudatory reviews–at least in Paris; Canada

was less receptive.

The following decade, in 1903, David Milne made a similar move, from the decidedly non-psychedelic Paisley, Ontario, to New York, where he studied at the Art Students’ League and later participated in the famous

1913 Duchamp urinal Armory Show. Milne’s career waned, and he ended up in the employ of a ski resort in Lake Placid in upstate New York before returning to Canada in 1928.

Mid-20th century, in 1952, William Ronald, in a true “hosehead”

Canadian success story, won a $1,000 hockey scholarship, allowing

him to study painting with Hans Hofmann in New York. In 1955, he

returned to New York, this time as a professional artist, where he

was quickly picked up by the prestigious Kootz Gallery, becoming,

one could say, the Wayne Gretzky of abstract expressionism. Ronald

stayed in New York until 1963, when Kootz ceased exhibiting his

work because the tide had turned to the less expressive style of

colourfield painting.

Three decades after Ronald’s prodigal return, sonic artist and musician Gordon Monahan received a DAAD scholarship (an invitational grant for foreign artists) from the German government. The scholarship, which has a reputation for bringing international artists to Berlin who never return home, resulted in Monahan and his partner, Laura Kikauka–whose electronically-animated horror vacuii installations are composed of dense layers of found kitsch–setting up permanent, part-time residence, dividing their time between Berlin and their farm near Meaford, Ontario, a permanent work of art called the Funny Farm (

see this art blog). Janet Cardiff and her husband/collaborator, Georges Bures Miller, also came to Berlin on a DAAD scholarship, the year after their prize-winning multimedia installation The Paradise Institute was shown at the 2001 Venice Biennale. They decided to stay in Berlin but like Monahan and Kikauka, they divide their time between Germany and Canada, returning to British Columbia for around six months each year.

Of course, the key difference between the three pre- and two

post-information age moves is that the latter aren’t complete

relocations. This is because of constantly increasing global

travel–virtual and physical, airline and online. The information

age has, for the art world, led collectively to what is now a

cliche: the artist as nomad. Ease of travel for people, art and

information has led to the perpetual growth of bienniales and

fairs, increased international interaction between gallery and

museum exhibitions and further international exchange through

artist residencies. Given the current prominence of art-world

nomadism, the notion of diaspora, true to the original Greek

meaning of “dispersion” not its later connotation of “exile”

doesn’t indicate a dividing line between home country and abroad, a

provincial “here” and a utopic “there” Rather, it denotes an

ever-shifting, definitively nomadic network.

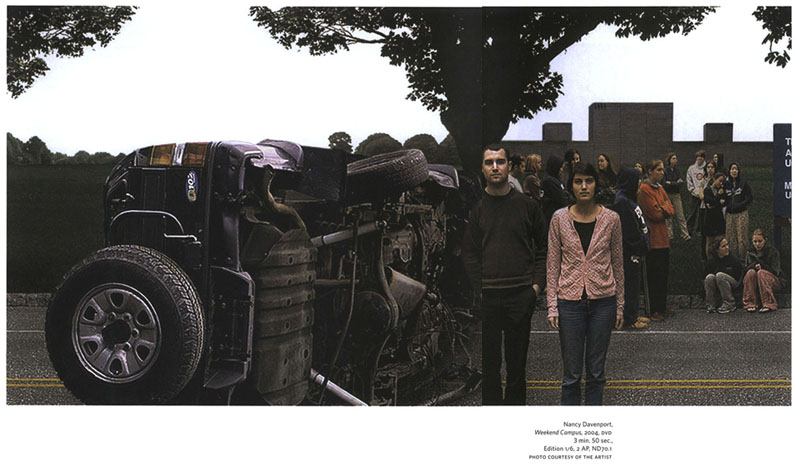

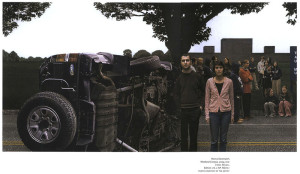

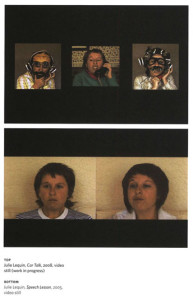

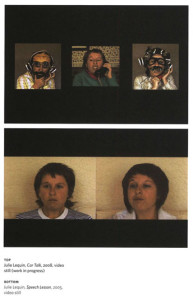

The internationalism of artists hot only begins with a relocation of professional art practice to the global stage but also through the increasingly long shopping list of residencies, scholarships and graduate programs available outside Canada. Take, for example, Julie Lequin (whose whimsical multimedia works sometimes deal directly with being a transplanted Quebecker in America) attending the Pasadena Art Centre and then staying on in Los Angeles. Shannon Bool, another Canadian, studied at the prestigious Stadelschule in Frankfurt and then moved to Berlin, where she continues to exhibit artworks that consider ornamentation in mass culture.

Berlin, especially, has an art buzz attracting Canadians (and

others) despite intense gentrification. Canadians in Berlin,

permanently or nomadically, include 2007 Sobey Prize winner Michel

de Broin, Bruce LaBruce, Angela Bulloch (who also resides in

London), Helen Cho, Karma Clark-Davis, Hadley and Maxwell, Rodney

LaTourelle, Monika Szewczyk and Jeremy Shaw.

Allan, an art critic and expat Canadian living in Berlin, notes that the city draws people largely because of the low rent, and a clime of freedom that fosters artistic experimentation. Kikauka points to the cultural energy of the city, and how it offers an extended education. Cardiff simply praises the city’s convenient location: you can fly or take a train anywhere in Europe in one or two hours. As well, Kikauka mentions practical matters, such as the ease of obtaining free materials for electro-mechanical sculptural work.

Then there’s LA’s developing scene. Along with Lequin, Canadian

artists such as Jon Pylypchuk, Eli Langer, Euan Macdonald and Mark

Verabioff reside there, a trend resulting from the growth of new

galleries, relatively cheap rent and a recent decade-or-so-long

tendency among LA collectors to buy local. Despite LA’s rising

status, New York remains a destination. However, escalating rents,

lack of medical coverage and the high cost of living discourage

most from taking up residence there. However, Karen Azoulay, AA

Bronson, David Craven, Chris Hanson and Hendrika Sonnenberg,

Terence Koh, Micah Lexier and numerous other Canadians reside in

New York or stay for extended periods of time. While London

surpasses New York in terres of living expense, it too has

attracted Canadians: David Altmejd, Anne Low, Dallas Seltz, Ingrid

Z. and Mark Lewis.

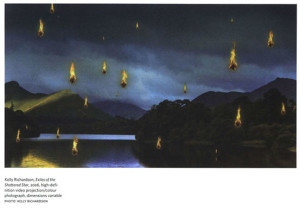

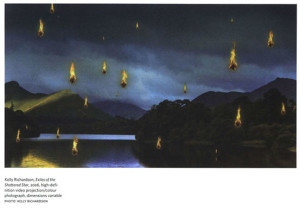

That most Canadian artists residing outside Canada settle in just a few major cities raises the question of just how much of a dispersion the Canadian diaspora truly is. Nonetheless, the cultural traffic passing through a major centre like New York allows at least for some transcendence of fixed place. So does the Internet. Much art dialogue has switched from bars, restaurants and openings to e-mails, websites and blogs. Besides, despite the cultural magnetism of established or emerging scenes, some expat Canadian artists reside elsewhere. Magdalen Celestino in Houston, Kelly Richardson in Newcastle, England and Robert Waters in Mexico City.

Dispersion, however, has a downside. Site-specific art practice,

which nomadism originally helped facilitate, is under threat

because of nomadism running rampant. As Miwon Kwon observes in One

Place After Another (2000), “The site is now structured

(inter)textually rather than spatially, and its model is not a map

but an itinerary … a nomadic narrative…” As a result, he

continues, “The artwork is becoming more and more ‘unhinged’ from

the actuality of the site …” Jumping from residency to

residency and from gallery to gallery, artists risk performing

cursory research and exhibiting superficial knowledge of given

sites.

For instance, Vanessa Beecroft can travel to Darfur–with a photographer, a studio assistant and an entire documentary film crew in tow–to produce Still Death! Darfur Still Deaf? for the 2007 Venice Biennale. A performance with her signature live models–in this case lithe Sudanese women sprayed with faux blood–it is torture-porn through a Vogue filter that exhibits little understanding of the ongoing Sudan crisis.

Another problem related to artists in transience is that the

liberation from living in a single location is inextricably tied to

the mechanisms of global capitalism. As Kwon notes, “while

site-specific art once defied commodification by insisting on

immobility, it now seems to espouse fluid mobility and nomadism for

the same purpose. But curiously, the nomadic principle also defines

capital and power in our rimes.”

Where nomadic art and money most visibly merge is, of course, the art market. Consider the consistently growing commercial spectacles of art fairs such as Miami-Basel that could be held anywhere there is a market, as the hyphenated, dual-city name implies.

What keeps the commercial art market in fixed places, however, is

a solid wealth base. While commercial success is a struggle

anywhere, New York and London, as well as Los Angeles and Berlin,

offer more opportunities than exist in Canada. Consider Chris

Hanson and Hendrika Sonnenberg’s comments: “because of the number of

commercial galleries and private collectors in the US, there are

just more ‘interested’ parties looking at art” than in Canada.

Commercial galleries often discover artists based on a reputation

they have gained through networking, and artists benefit from

living in the same city as their dealers. Would David Altmejd, for

instance, have been picked up by Andrea Rosen (herself a Canadian)

had he stayed in Montreal, and would he have subsequently

represented Canada at the 2007 Venice Biennale? Julie Lequin

observes that in Los Angeles, while things are still difficult

financially for an emerging artist, a real hope of eventually

making a good living serves as a powerful motivator. Kikauka

stresses the importance of her gallerist, the DNA gallery in

Berlin: along with exhibiting and selling her work, the DNA has

also been able to

exhibit it in numerous galleries and museums.

“This is essential for my art production” she notes, as “I get

commissions for permanent or travelling shows” Conversely, being a

relatively low-population country lacking an established public

appreciation of contemporary art, Canada’s art market is small.

The question for artists who tap into globalism to make a living from their art is how to maintain a meaningful, if not critical, practice within this reactionary structure. Exemplary of a critical approach to this problem is Scottish artist Simon Stading’s careful researching of place that led to the wonderfully wry Infestation Piece (Musselled Moore) (2007-08). Starling submerged a reproduction of a Henry Moore sculpture owned by the Art Gallery of Ontario in Lake Ontario, allowing an art work from colonial Britain that had “invaded” a Canadian gallery to be infested by zebra mussels, another colonizer. Thus Starling effectively raises issues of colonization and the obscuring of local cultural identity relevant to global capitalism.

One tack some Canadian artists have taken that’s not critical but is comparatively effective for making use of a foreign context is presenting Canadian imagery in a new locale and, consequently, drawing new meanings. Cardiff and Bures Miller’s Night Canoeing (2004) and Road Trip (2004) make use of the typical Canadian scenes their titles denote, and Hanson and Sonnenberg exhibit hockey icons and images, from a zamboni sculpture to a hockey-fight video.

Canadian artists abroad have been equally successful at

countering assumed national tropes. Canada is too often

stereotyped as a White country, a former British colony under

the cultural spell of Middle-American mass culture. Canadian

artists of colour working outside Canada, therefore,

experience amplified displacement because of the

misidentification added to the move.

Yet misidentification provides a tremendous opportunity for righting stereotypes. Take the now celebrity-status Terence Koh, who maintains his Asian Punkboy website and who had a solo exhibition at the Whitney last year. Koh collaborated with Bruce LaBruce, the quintessential queer-punk nomad, to put on the exhibition Blame Canada at Peres Projects in Berlin in 2007, a response to a conservative American perception of Canada. To quote from their press release:

The US makes a habit of blaming Canada for a variety of nasty

things: a porous border, lax immigration policies, Communist

tendencies, multiculturalism, gayness, Celine Dion. So why not give

them what they want: a scapegoat, a whipping boy, a lapdog, a

masochist, a Judas, a boot-licker, a cocksucker, a punk. In fact,

why not give them two–Terrence Koh and Bruce LaBruce–two of the

biggest faggots this side of Elton John.

While projects like

Blame Canada provide effective cultural ambassadorship, the growing number of Canadian artists outside of Canada raises fears of a brain drain. Jennifer Mien, for one, worries if Canadian artists keep moving to Berlin and elsewhere, the Canadian art community will surfer. I’m not concerned. Actually, the best thing Canada can do for its art is encourage its artists to leave–at least temporarily.

Despite providing more government funding than some countries,

Canada is an expensive place to live. As Kelly Richardson explains,

“the ease of living in the UK compared to Toronto has allowed me to

focus on the development of my work. It would not have been

remotely possible to do what I do here, living in Toronto–or

possibly anywhere else in Canada”

Canada continually elects culturally disinterested governments.

Grants for artists do not provide a sustainable living, and when

you take inflation into account their value is continually on the

decrease. Yes, Canada has largely government-funded artist-run

centres, but artists obviously need to be able to afford to exhibit

in them. Support for building an art market and more aggressive tax

incentives for philanthropic donations, among other initiatives,

are needed, but it is unlikely that they will be implemented,

certainly not by the Harper government. We also need cultural

policies that suit this era of increased artists’ mobility, for

instance the funding of cultural exchanges and artists residencies

in Canada.

Unsurprisingly, Canada’s public shares the same daunting lack of interest in contemporary art as the government it elected. Richardson points out that in contrast, “the UK has gone to great lengths to involve the greater public in contemporary art” and “the result is that most people are in some way familiar with it: She continues, “it’s been quite inspiring to be part of a culture much more actively engaged with art; this has definitely affected my decision to stay.”

Combined with a failure to maintain a cultural climate “in here”

is a failure to get Canadian art “out there.” Despite the

internationalization of the art world, Canadian numbers at the

major bienniales such as Venice and Sao Paulo are low; at the

recent 2008 Carnegie International, the number was zero. Canadian

dealers exhibiting in the major fairs such as ARCO and Miami-Basel

are few (two Canadian dealers exhibited at ARCO 2008, and just one

Canadian dealer will exhibit at Miami-Basel 2008). The question of

who is to blame merits an essay in itself, but no finger-pointing

is needed to conclude that this lack of global presence means

Canada is a country that isolates its artists within a culture that

fails to notice them.

Lobbying unresponsive governments to educate an unresponsive

public or passively accepting an inability to maintain a

full-time, internationally visible art practice is not patriotic,

it is masochistic. If nothing else, a brain drain could make the

public and the government aware of just how much Canada

undervalues its artists. In the meantime, the Canadian diaspora

actually does have as much to do with forced exile as it does

with dispersion.

The following decade, in 1903, David Milne made a similar move, from the decidedly non-psychedelic Paisley, Ontario, to New York, where he studied at the Art Students’ League and later participated in the famous 1913 Duchamp urinal Armory Show. Milne’s career waned, and he ended up in the employ of a ski resort in Lake Placid in upstate New York before returning to Canada in 1928.

Mid-20th century, in 1952, William Ronald, in a true “hosehead”

Canadian success story, won a $1,000 hockey scholarship, allowing

him to study painting with Hans Hofmann in New York. In 1955, he

returned to New York, this time as a professional artist, where he

was quickly picked up by the prestigious Kootz Gallery, becoming,

one could say, the Wayne Gretzky of abstract expressionism. Ronald

stayed in New York until 1963, when Kootz ceased exhibiting his

work because the tide had turned to the less expressive style of

colourfield painting.

Three decades after Ronald’s prodigal return, sonic artist and musician Gordon Monahan received a DAAD scholarship (an invitational grant for foreign artists) from the German government. The scholarship, which has a reputation for bringing international artists to Berlin who never return home, resulted in Monahan and his partner, Laura Kikauka–whose electronically-animated horror vacuii installations are composed of dense layers of found kitsch–setting up permanent, part-time residence, dividing their time between Berlin and their farm near Meaford, Ontario, a permanent work of art called the Funny Farm (see this art blog). Janet Cardiff and her husband/collaborator, Georges Bures Miller, also came to Berlin on a DAAD scholarship, the year after their prize-winning multimedia installation The Paradise Institute was shown at the 2001 Venice Biennale. They decided to stay in Berlin but like Monahan and Kikauka, they divide their time between Germany and Canada, returning to British Columbia for around six months each year.

Of course, the key difference between the three pre- and two

post-information age moves is that the latter aren’t complete

relocations. This is because of constantly increasing global

travel–virtual and physical, airline and online. The information

age has, for the art world, led collectively to what is now a

cliche: the artist as nomad. Ease of travel for people, art and

information has led to the perpetual growth of bienniales and

fairs, increased international interaction between gallery and

museum exhibitions and further international exchange through

artist residencies. Given the current prominence of art-world

nomadism, the notion of diaspora, true to the original Greek

meaning of “dispersion” not its later connotation of “exile”

doesn’t indicate a dividing line between home country and abroad, a

provincial “here” and a utopic “there” Rather, it denotes an

ever-shifting, definitively nomadic network.

The following decade, in 1903, David Milne made a similar move, from the decidedly non-psychedelic Paisley, Ontario, to New York, where he studied at the Art Students’ League and later participated in the famous 1913 Duchamp urinal Armory Show. Milne’s career waned, and he ended up in the employ of a ski resort in Lake Placid in upstate New York before returning to Canada in 1928.

Mid-20th century, in 1952, William Ronald, in a true “hosehead”

Canadian success story, won a $1,000 hockey scholarship, allowing

him to study painting with Hans Hofmann in New York. In 1955, he

returned to New York, this time as a professional artist, where he

was quickly picked up by the prestigious Kootz Gallery, becoming,

one could say, the Wayne Gretzky of abstract expressionism. Ronald

stayed in New York until 1963, when Kootz ceased exhibiting his

work because the tide had turned to the less expressive style of

colourfield painting.

Three decades after Ronald’s prodigal return, sonic artist and musician Gordon Monahan received a DAAD scholarship (an invitational grant for foreign artists) from the German government. The scholarship, which has a reputation for bringing international artists to Berlin who never return home, resulted in Monahan and his partner, Laura Kikauka–whose electronically-animated horror vacuii installations are composed of dense layers of found kitsch–setting up permanent, part-time residence, dividing their time between Berlin and their farm near Meaford, Ontario, a permanent work of art called the Funny Farm (see this art blog). Janet Cardiff and her husband/collaborator, Georges Bures Miller, also came to Berlin on a DAAD scholarship, the year after their prize-winning multimedia installation The Paradise Institute was shown at the 2001 Venice Biennale. They decided to stay in Berlin but like Monahan and Kikauka, they divide their time between Germany and Canada, returning to British Columbia for around six months each year.

Of course, the key difference between the three pre- and two

post-information age moves is that the latter aren’t complete

relocations. This is because of constantly increasing global

travel–virtual and physical, airline and online. The information

age has, for the art world, led collectively to what is now a

cliche: the artist as nomad. Ease of travel for people, art and

information has led to the perpetual growth of bienniales and

fairs, increased international interaction between gallery and

museum exhibitions and further international exchange through

artist residencies. Given the current prominence of art-world

nomadism, the notion of diaspora, true to the original Greek

meaning of “dispersion” not its later connotation of “exile”

doesn’t indicate a dividing line between home country and abroad, a

provincial “here” and a utopic “there” Rather, it denotes an

ever-shifting, definitively nomadic network.

The internationalism of artists hot only begins with a relocation of professional art practice to the global stage but also through the increasingly long shopping list of residencies, scholarships and graduate programs available outside Canada. Take, for example, Julie Lequin (whose whimsical multimedia works sometimes deal directly with being a transplanted Quebecker in America) attending the Pasadena Art Centre and then staying on in Los Angeles. Shannon Bool, another Canadian, studied at the prestigious Stadelschule in Frankfurt and then moved to Berlin, where she continues to exhibit artworks that consider ornamentation in mass culture.

Berlin, especially, has an art buzz attracting Canadians (and

others) despite intense gentrification. Canadians in Berlin,

permanently or nomadically, include 2007 Sobey Prize winner Michel

de Broin, Bruce LaBruce, Angela Bulloch (who also resides in

London), Helen Cho, Karma Clark-Davis, Hadley and Maxwell, Rodney

LaTourelle, Monika Szewczyk and Jeremy Shaw.

Allan, an art critic and expat Canadian living in Berlin, notes that the city draws people largely because of the low rent, and a clime of freedom that fosters artistic experimentation. Kikauka points to the cultural energy of the city, and how it offers an extended education. Cardiff simply praises the city’s convenient location: you can fly or take a train anywhere in Europe in one or two hours. As well, Kikauka mentions practical matters, such as the ease of obtaining free materials for electro-mechanical sculptural work.

Then there’s LA’s developing scene. Along with Lequin, Canadian

artists such as Jon Pylypchuk, Eli Langer, Euan Macdonald and Mark

Verabioff reside there, a trend resulting from the growth of new

galleries, relatively cheap rent and a recent decade-or-so-long

tendency among LA collectors to buy local. Despite LA’s rising

status, New York remains a destination. However, escalating rents,

lack of medical coverage and the high cost of living discourage

most from taking up residence there. However, Karen Azoulay, AA

Bronson, David Craven, Chris Hanson and Hendrika Sonnenberg,

Terence Koh, Micah Lexier and numerous other Canadians reside in

New York or stay for extended periods of time. While London

surpasses New York in terres of living expense, it too has

attracted Canadians: David Altmejd, Anne Low, Dallas Seltz, Ingrid

Z. and Mark Lewis.

That most Canadian artists residing outside Canada settle in just a few major cities raises the question of just how much of a dispersion the Canadian diaspora truly is. Nonetheless, the cultural traffic passing through a major centre like New York allows at least for some transcendence of fixed place. So does the Internet. Much art dialogue has switched from bars, restaurants and openings to e-mails, websites and blogs. Besides, despite the cultural magnetism of established or emerging scenes, some expat Canadian artists reside elsewhere. Magdalen Celestino in Houston, Kelly Richardson in Newcastle, England and Robert Waters in Mexico City.

Dispersion, however, has a downside. Site-specific art practice,

which nomadism originally helped facilitate, is under threat

because of nomadism running rampant. As Miwon Kwon observes in One

Place After Another (2000), “The site is now structured

(inter)textually rather than spatially, and its model is not a map

but an itinerary … a nomadic narrative…” As a result, he

continues, “The artwork is becoming more and more ‘unhinged’ from

the actuality of the site …” Jumping from residency to

residency and from gallery to gallery, artists risk performing

cursory research and exhibiting superficial knowledge of given

sites.

For instance, Vanessa Beecroft can travel to Darfur–with a photographer, a studio assistant and an entire documentary film crew in tow–to produce Still Death! Darfur Still Deaf? for the 2007 Venice Biennale. A performance with her signature live models–in this case lithe Sudanese women sprayed with faux blood–it is torture-porn through a Vogue filter that exhibits little understanding of the ongoing Sudan crisis.

Another problem related to artists in transience is that the

liberation from living in a single location is inextricably tied to

the mechanisms of global capitalism. As Kwon notes, “while

site-specific art once defied commodification by insisting on

immobility, it now seems to espouse fluid mobility and nomadism for

the same purpose. But curiously, the nomadic principle also defines

capital and power in our rimes.”

The internationalism of artists hot only begins with a relocation of professional art practice to the global stage but also through the increasingly long shopping list of residencies, scholarships and graduate programs available outside Canada. Take, for example, Julie Lequin (whose whimsical multimedia works sometimes deal directly with being a transplanted Quebecker in America) attending the Pasadena Art Centre and then staying on in Los Angeles. Shannon Bool, another Canadian, studied at the prestigious Stadelschule in Frankfurt and then moved to Berlin, where she continues to exhibit artworks that consider ornamentation in mass culture.

Berlin, especially, has an art buzz attracting Canadians (and

others) despite intense gentrification. Canadians in Berlin,

permanently or nomadically, include 2007 Sobey Prize winner Michel

de Broin, Bruce LaBruce, Angela Bulloch (who also resides in

London), Helen Cho, Karma Clark-Davis, Hadley and Maxwell, Rodney

LaTourelle, Monika Szewczyk and Jeremy Shaw.

Allan, an art critic and expat Canadian living in Berlin, notes that the city draws people largely because of the low rent, and a clime of freedom that fosters artistic experimentation. Kikauka points to the cultural energy of the city, and how it offers an extended education. Cardiff simply praises the city’s convenient location: you can fly or take a train anywhere in Europe in one or two hours. As well, Kikauka mentions practical matters, such as the ease of obtaining free materials for electro-mechanical sculptural work.

Then there’s LA’s developing scene. Along with Lequin, Canadian

artists such as Jon Pylypchuk, Eli Langer, Euan Macdonald and Mark

Verabioff reside there, a trend resulting from the growth of new

galleries, relatively cheap rent and a recent decade-or-so-long

tendency among LA collectors to buy local. Despite LA’s rising

status, New York remains a destination. However, escalating rents,

lack of medical coverage and the high cost of living discourage

most from taking up residence there. However, Karen Azoulay, AA

Bronson, David Craven, Chris Hanson and Hendrika Sonnenberg,

Terence Koh, Micah Lexier and numerous other Canadians reside in

New York or stay for extended periods of time. While London

surpasses New York in terres of living expense, it too has

attracted Canadians: David Altmejd, Anne Low, Dallas Seltz, Ingrid

Z. and Mark Lewis.

That most Canadian artists residing outside Canada settle in just a few major cities raises the question of just how much of a dispersion the Canadian diaspora truly is. Nonetheless, the cultural traffic passing through a major centre like New York allows at least for some transcendence of fixed place. So does the Internet. Much art dialogue has switched from bars, restaurants and openings to e-mails, websites and blogs. Besides, despite the cultural magnetism of established or emerging scenes, some expat Canadian artists reside elsewhere. Magdalen Celestino in Houston, Kelly Richardson in Newcastle, England and Robert Waters in Mexico City.

Dispersion, however, has a downside. Site-specific art practice,

which nomadism originally helped facilitate, is under threat

because of nomadism running rampant. As Miwon Kwon observes in One

Place After Another (2000), “The site is now structured

(inter)textually rather than spatially, and its model is not a map

but an itinerary … a nomadic narrative…” As a result, he

continues, “The artwork is becoming more and more ‘unhinged’ from

the actuality of the site …” Jumping from residency to

residency and from gallery to gallery, artists risk performing

cursory research and exhibiting superficial knowledge of given

sites.

For instance, Vanessa Beecroft can travel to Darfur–with a photographer, a studio assistant and an entire documentary film crew in tow–to produce Still Death! Darfur Still Deaf? for the 2007 Venice Biennale. A performance with her signature live models–in this case lithe Sudanese women sprayed with faux blood–it is torture-porn through a Vogue filter that exhibits little understanding of the ongoing Sudan crisis.

Another problem related to artists in transience is that the

liberation from living in a single location is inextricably tied to

the mechanisms of global capitalism. As Kwon notes, “while

site-specific art once defied commodification by insisting on

immobility, it now seems to espouse fluid mobility and nomadism for

the same purpose. But curiously, the nomadic principle also defines

capital and power in our rimes.”

Where nomadic art and money most visibly merge is, of course, the art market. Consider the consistently growing commercial spectacles of art fairs such as Miami-Basel that could be held anywhere there is a market, as the hyphenated, dual-city name implies.

What keeps the commercial art market in fixed places, however, is

a solid wealth base. While commercial success is a struggle

anywhere, New York and London, as well as Los Angeles and Berlin,

offer more opportunities than exist in Canada. Consider Chris

Hanson and Hendrika Sonnenberg’s comments: “because of the number of

commercial galleries and private collectors in the US, there are

just more ‘interested’ parties looking at art” than in Canada.

Commercial galleries often discover artists based on a reputation

they have gained through networking, and artists benefit from

living in the same city as their dealers. Would David Altmejd, for

instance, have been picked up by Andrea Rosen (herself a Canadian)

had he stayed in Montreal, and would he have subsequently

represented Canada at the 2007 Venice Biennale? Julie Lequin

observes that in Los Angeles, while things are still difficult

financially for an emerging artist, a real hope of eventually

making a good living serves as a powerful motivator. Kikauka

stresses the importance of her gallerist, the DNA gallery in

Berlin: along with exhibiting and selling her work, the DNA has

also been able to exhibit it in numerous galleries and museums.

“This is essential for my art production” she notes, as “I get

commissions for permanent or travelling shows” Conversely, being a

relatively low-population country lacking an established public

appreciation of contemporary art, Canada’s art market is small.

The question for artists who tap into globalism to make a living from their art is how to maintain a meaningful, if not critical, practice within this reactionary structure. Exemplary of a critical approach to this problem is Scottish artist Simon Stading’s careful researching of place that led to the wonderfully wry Infestation Piece (Musselled Moore) (2007-08). Starling submerged a reproduction of a Henry Moore sculpture owned by the Art Gallery of Ontario in Lake Ontario, allowing an art work from colonial Britain that had “invaded” a Canadian gallery to be infested by zebra mussels, another colonizer. Thus Starling effectively raises issues of colonization and the obscuring of local cultural identity relevant to global capitalism.

One tack some Canadian artists have taken that’s not critical but is comparatively effective for making use of a foreign context is presenting Canadian imagery in a new locale and, consequently, drawing new meanings. Cardiff and Bures Miller’s Night Canoeing (2004) and Road Trip (2004) make use of the typical Canadian scenes their titles denote, and Hanson and Sonnenberg exhibit hockey icons and images, from a zamboni sculpture to a hockey-fight video.

Canadian artists abroad have been equally successful at

countering assumed national tropes. Canada is too often

stereotyped as a White country, a former British colony under

the cultural spell of Middle-American mass culture. Canadian

artists of colour working outside Canada, therefore,

experience amplified displacement because of the

misidentification added to the move.

Yet misidentification provides a tremendous opportunity for righting stereotypes. Take the now celebrity-status Terence Koh, who maintains his Asian Punkboy website and who had a solo exhibition at the Whitney last year. Koh collaborated with Bruce LaBruce, the quintessential queer-punk nomad, to put on the exhibition Blame Canada at Peres Projects in Berlin in 2007, a response to a conservative American perception of Canada. To quote from their press release:

The US makes a habit of blaming Canada for a variety of nasty

things: a porous border, lax immigration policies, Communist

tendencies, multiculturalism, gayness, Celine Dion. So why not give

them what they want: a scapegoat, a whipping boy, a lapdog, a

masochist, a Judas, a boot-licker, a cocksucker, a punk. In fact,

why not give them two–Terrence Koh and Bruce LaBruce–two of the

biggest faggots this side of Elton John.

While projects like Blame Canada provide effective cultural ambassadorship, the growing number of Canadian artists outside of Canada raises fears of a brain drain. Jennifer Mien, for one, worries if Canadian artists keep moving to Berlin and elsewhere, the Canadian art community will surfer. I’m not concerned. Actually, the best thing Canada can do for its art is encourage its artists to leave–at least temporarily.

Despite providing more government funding than some countries,

Canada is an expensive place to live. As Kelly Richardson explains,

“the ease of living in the UK compared to Toronto has allowed me to

focus on the development of my work. It would not have been

remotely possible to do what I do here, living in Toronto–or

possibly anywhere else in Canada”

Canada continually elects culturally disinterested governments.

Grants for artists do not provide a sustainable living, and when

you take inflation into account their value is continually on the

decrease. Yes, Canada has largely government-funded artist-run

centres, but artists obviously need to be able to afford to exhibit

in them. Support for building an art market and more aggressive tax

incentives for philanthropic donations, among other initiatives,

are needed, but it is unlikely that they will be implemented,

certainly not by the Harper government. We also need cultural

policies that suit this era of increased artists’ mobility, for

instance the funding of cultural exchanges and artists residencies

in Canada.

Unsurprisingly, Canada’s public shares the same daunting lack of interest in contemporary art as the government it elected. Richardson points out that in contrast, “the UK has gone to great lengths to involve the greater public in contemporary art” and “the result is that most people are in some way familiar with it: She continues, “it’s been quite inspiring to be part of a culture much more actively engaged with art; this has definitely affected my decision to stay.”

Combined with a failure to maintain a cultural climate “in here”

is a failure to get Canadian art “out there.” Despite the

internationalization of the art world, Canadian numbers at the

major bienniales such as Venice and Sao Paulo are low; at the

recent 2008 Carnegie International, the number was zero. Canadian

dealers exhibiting in the major fairs such as ARCO and Miami-Basel

are few (two Canadian dealers exhibited at ARCO 2008, and just one

Canadian dealer will exhibit at Miami-Basel 2008). The question of

who is to blame merits an essay in itself, but no finger-pointing

is needed to conclude that this lack of global presence means

Canada is a country that isolates its artists within a culture that

fails to notice them.

Lobbying unresponsive governments to educate an unresponsive

public or passively accepting an inability to maintain a

full-time, internationally visible art practice is not patriotic,

it is masochistic. If nothing else, a brain drain could make the

public and the government aware of just how much Canada

undervalues its artists. In the meantime, the Canadian diaspora

actually does have as much to do with forced exile as it does

with dispersion.

Where nomadic art and money most visibly merge is, of course, the art market. Consider the consistently growing commercial spectacles of art fairs such as Miami-Basel that could be held anywhere there is a market, as the hyphenated, dual-city name implies.

What keeps the commercial art market in fixed places, however, is

a solid wealth base. While commercial success is a struggle

anywhere, New York and London, as well as Los Angeles and Berlin,

offer more opportunities than exist in Canada. Consider Chris

Hanson and Hendrika Sonnenberg’s comments: “because of the number of

commercial galleries and private collectors in the US, there are

just more ‘interested’ parties looking at art” than in Canada.

Commercial galleries often discover artists based on a reputation

they have gained through networking, and artists benefit from

living in the same city as their dealers. Would David Altmejd, for

instance, have been picked up by Andrea Rosen (herself a Canadian)

had he stayed in Montreal, and would he have subsequently

represented Canada at the 2007 Venice Biennale? Julie Lequin

observes that in Los Angeles, while things are still difficult

financially for an emerging artist, a real hope of eventually

making a good living serves as a powerful motivator. Kikauka

stresses the importance of her gallerist, the DNA gallery in

Berlin: along with exhibiting and selling her work, the DNA has

also been able to exhibit it in numerous galleries and museums.

“This is essential for my art production” she notes, as “I get

commissions for permanent or travelling shows” Conversely, being a

relatively low-population country lacking an established public

appreciation of contemporary art, Canada’s art market is small.

The question for artists who tap into globalism to make a living from their art is how to maintain a meaningful, if not critical, practice within this reactionary structure. Exemplary of a critical approach to this problem is Scottish artist Simon Stading’s careful researching of place that led to the wonderfully wry Infestation Piece (Musselled Moore) (2007-08). Starling submerged a reproduction of a Henry Moore sculpture owned by the Art Gallery of Ontario in Lake Ontario, allowing an art work from colonial Britain that had “invaded” a Canadian gallery to be infested by zebra mussels, another colonizer. Thus Starling effectively raises issues of colonization and the obscuring of local cultural identity relevant to global capitalism.

One tack some Canadian artists have taken that’s not critical but is comparatively effective for making use of a foreign context is presenting Canadian imagery in a new locale and, consequently, drawing new meanings. Cardiff and Bures Miller’s Night Canoeing (2004) and Road Trip (2004) make use of the typical Canadian scenes their titles denote, and Hanson and Sonnenberg exhibit hockey icons and images, from a zamboni sculpture to a hockey-fight video.

Canadian artists abroad have been equally successful at

countering assumed national tropes. Canada is too often

stereotyped as a White country, a former British colony under

the cultural spell of Middle-American mass culture. Canadian

artists of colour working outside Canada, therefore,

experience amplified displacement because of the

misidentification added to the move.

Yet misidentification provides a tremendous opportunity for righting stereotypes. Take the now celebrity-status Terence Koh, who maintains his Asian Punkboy website and who had a solo exhibition at the Whitney last year. Koh collaborated with Bruce LaBruce, the quintessential queer-punk nomad, to put on the exhibition Blame Canada at Peres Projects in Berlin in 2007, a response to a conservative American perception of Canada. To quote from their press release:

The US makes a habit of blaming Canada for a variety of nasty

things: a porous border, lax immigration policies, Communist

tendencies, multiculturalism, gayness, Celine Dion. So why not give

them what they want: a scapegoat, a whipping boy, a lapdog, a

masochist, a Judas, a boot-licker, a cocksucker, a punk. In fact,

why not give them two–Terrence Koh and Bruce LaBruce–two of the

biggest faggots this side of Elton John.

While projects like Blame Canada provide effective cultural ambassadorship, the growing number of Canadian artists outside of Canada raises fears of a brain drain. Jennifer Mien, for one, worries if Canadian artists keep moving to Berlin and elsewhere, the Canadian art community will surfer. I’m not concerned. Actually, the best thing Canada can do for its art is encourage its artists to leave–at least temporarily.

Despite providing more government funding than some countries,

Canada is an expensive place to live. As Kelly Richardson explains,

“the ease of living in the UK compared to Toronto has allowed me to

focus on the development of my work. It would not have been

remotely possible to do what I do here, living in Toronto–or

possibly anywhere else in Canada”

Canada continually elects culturally disinterested governments.

Grants for artists do not provide a sustainable living, and when

you take inflation into account their value is continually on the

decrease. Yes, Canada has largely government-funded artist-run

centres, but artists obviously need to be able to afford to exhibit

in them. Support for building an art market and more aggressive tax

incentives for philanthropic donations, among other initiatives,

are needed, but it is unlikely that they will be implemented,

certainly not by the Harper government. We also need cultural

policies that suit this era of increased artists’ mobility, for

instance the funding of cultural exchanges and artists residencies

in Canada.

Unsurprisingly, Canada’s public shares the same daunting lack of interest in contemporary art as the government it elected. Richardson points out that in contrast, “the UK has gone to great lengths to involve the greater public in contemporary art” and “the result is that most people are in some way familiar with it: She continues, “it’s been quite inspiring to be part of a culture much more actively engaged with art; this has definitely affected my decision to stay.”

Combined with a failure to maintain a cultural climate “in here”

is a failure to get Canadian art “out there.” Despite the

internationalization of the art world, Canadian numbers at the

major bienniales such as Venice and Sao Paulo are low; at the

recent 2008 Carnegie International, the number was zero. Canadian

dealers exhibiting in the major fairs such as ARCO and Miami-Basel

are few (two Canadian dealers exhibited at ARCO 2008, and just one

Canadian dealer will exhibit at Miami-Basel 2008). The question of

who is to blame merits an essay in itself, but no finger-pointing

is needed to conclude that this lack of global presence means

Canada is a country that isolates its artists within a culture that

fails to notice them.

Lobbying unresponsive governments to educate an unresponsive

public or passively accepting an inability to maintain a

full-time, internationally visible art practice is not patriotic,

it is masochistic. If nothing else, a brain drain could make the

public and the government aware of just how much Canada

undervalues its artists. In the meantime, the Canadian diaspora

actually does have as much to do with forced exile as it does

with dispersion.