Federal elections, Olympic ceremonies, the actions of a unit of sharp shooters, a theater premiere–all count as public events. Other events of overwhelming public significance, such as child rearing, factory work, and watching television within one’s own four walls, are considered private. The real social experiences of human beings, produced in everyday life and work cut across such divisions.

–Alexander Kluge and Oskar Negt

According to the official countdown clock that stands in front of the

Dalet Art Gallery, at the time of writing, there are 245 days until the 2010 Olympic Winter Games. Along with the lead-up to the Games have come concerns about rising eviction rates, as many landlords are trying to profit from the short window during which tourists will be willing to pay many times the market value for their residential spaces. While this kind of behaviour is sure to increase in the coming months, it is nothing new; Vancouver landlords commonly use “renovations” as an excuse for raising rents by such a large margin that it is often tantamount to eviction.

Ten years ago, a set of row houses on Hawks Avenue in Vancouver’s Strathcona neighbourhood was being cleared for “renovations.” In response to this upheaval, artists who were living there took the opportunity to organize a large exhibition in two of the houses, which they called The Empty Home Show. The main and upper floors of both houses were crammed full of works by over 30 local artists, however the work that stands out most clearly in my memory was a piece by Scott Evans and Jason McLean, installed in a dark basement. The artists had excavated a portion of the floor and foundation, and created a sculptural, subterranean world of moss and mushrooms that encircled a watery cesspool. It seemed that this swamp-work might have always existed there, like a memory materialized from the last vestiges of eastern False Creek, which once ran within metres of Hawks Avenue.

Before it was drained and filled in to make way for a railyard, False Creek was a crucial part of the surrounding communities, supporting a range of industries and separating the neighbourhoods of Strathcona and Mount Pleasant. With the exception of a short portage through a ravine on the east side of Strathcona, there was once a time when you could circumnavigate Vancouver’s entire downtown peninsula by boat. A few blocks from this ravine is the site of another exhibition space, this one created by Aaron Carpenter, Miguel da Conceicao, and Jonathan Middleton in 2006 in the front room of their Strathcona home.

The name of this space, The Bodgers’ and Kludgers’ Co-operative Art Parlour, points to the domestic parlour as a place of leisure, while invoking the participation of a community. A bodger or a kludger is someone who builds things with available materials in a somewhat shoddy manner, but for the proprietors of the Art Parlour it also evokes expertise based on direct experience, coupled with a free-form sensibility. The bodger or kludger’s practice is linked to an earlier mode of localized, individual production that has become increasingly alienated. To make do with scavenged materials requires an intimate knowledge of the contingencies of one’s immediate environment, and is an act that is both leisure and labour.

The first thing the Oxford English Dictionary tells us about the noun “parlour” is that it is a dated term. This is true of the physical space of a parlour, as well: the Victorian or Edwardian parlour was a designated place of leisure, activated through social gatherings and games, or individual pursuits such as reading. Theodor Adorno points out that the term “leisure” is itself also outdated, and is distinctly different from the more recently coined expression “free time,” which is imbued with the illusion of freedom, but is directly linked to the hegemonic consumerist structures of advanced capitalism. Adorno notes that “… its precursor, the term ‘leisure’ denoted the privilege of an unconstrained, comfortable life-style, hence something qualitatively different and far more auspicious–[free time] indicates a specific difference, that of time which is neither free nor spare, which is occupied by work, and which moreover one could designate as heteronomous. Free time is shackled to its opposite.” For Adorno, hobbies are activities that are associated with “free time,” and having one simply fills the void between work and more work, thus distracting the practitioner from productive social or political engagement. The societal anxiety around real free time is clearly articulated by the growth of the so-called hobby industry, an economic juggernaut that in recent years has spawned a Michaels craft store in every suburb. As Adorno suggests of his own practices outside of official working hours, “Making music, listening to music, reading with all my attention, these activities are part and parcel of my life; to call them hobbies would make a mockery of them.” Since all three of these activities have, in different ways, contributed to his theoretical output, their productivity removes them from the realm of hobby. Adorno, through his practice, rejects the reified sphere of “free time,” and instead acts as if leisure never went out of style.

The inaugural exhibition at BKCAV, a solo show by Vancouver artist Steven Brekelmans called Kit Bashing that opened in August 2006, complicated the boundaries between labour and leisure. Brekelmans created a full-scale set of drums and a guitar amp out of balsa wood and paper, materials typically used for making model airplanes. “Kit bashing” is the practice where enthusiasts take commercially available models and modify them to suit their needs. Through the act of incorporating the construction of a model into his art practice, Brekelroans literally turned a hobby into labour and then back into a signifier of lost leisure: a drum kit that is impossible to play without bashing it into total destruction. This layered improvisational practice seemed to set the tone for the entire BKCAP project.

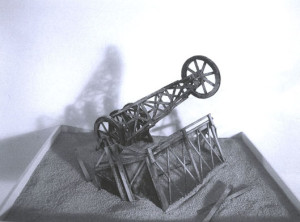

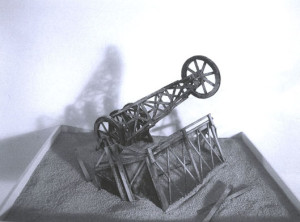

BKCAP’S second art exhibition was titled Beholding the tranquil beauty and brilliancy of the ocean’s skin, one forgets the tiger heart that pants beneath it; and would not willingly remember that this velvet paw but conceals a remorseless fang, a maritime-themed exhibition named after a line from Herman Melville’s Moby Dick. Curated by Carpenter and Middleton, this show included works by Sarah Edmonds, Angus Ferguson, Heather and Ivan Morrison, Neil Wedman, and Rhonda Weppler and Trevor Mahovsky. Works like the latter pair’s maquette for Thirty Foot Canoe Yawl (2006), a veneer skin of a sailboat that collapsed upon itself, and Ferguson’s Bruce’s Secret (2006), a miniature replica of the winch used to hoist the notoriously malfunctioning mechanical shark used in the film Jaws, articulate the futility of representing the nautical sublime. These models of failure sat nicely against the backdrop of a parlour: the traditional home of the armchair traveller, a place where miniature ships are stranded in rum bottles, nautical epics are read from front to back, and dwellers pull anchor to float alongside the shores of boredom.

The spaces that I describe here and refer to as contingent spaces sit parallel to established galleries and artist-run centres. A significant part of contemporary curatorial practice involves negotiating between the support and bureaucracy of institutions and the freedom and instability provided by independent projects such as The Empty Home Show and

Art Online. The negotiation required reflects how curating has changed over the last 35-40 years from a job almost invariably linked to a museum or another art institution to a practice that does not need to be connected to any place at all. During this same time, artist-run centres in Vancouver and across Canada have gone from being ostensibly radical assertions of artists’ independence from curators and institutions to being established organizations offering more or less stable employment to trained directorial and/or curatorial staff. But this bureaucratization often restricts the possibilities for spontaneous, context-responsive curatorial practices, especially given that an institution’s long-term stability is a necessary criterion in the eyes of funding bodies. As curator and writer Carlos Basualdo states, “For their survival institutions require the illusion of everlastingness, since this is what, in the final analysis, safeguards them against their contingent character.”

Artist-run centres do occasionally engage with external, site-specific programming. Projects including Out of Office Reply, Sydney Hermant’s series of site-specific residencies through the OR Gallery in 2005, and Melanie O’Brian’s current OFFSITE program through Artspeak facilitate interventions within provisional spaces. These projects take place not only because of hard work and innovative directorial vision, but also because these centres have proven their long-term stability. Such site-specific initiatives require a lot of advance planning and are almost invariably anchored back to the context of an institution. However, these practices provide frameworks for some of the most engaging contemporary art in Canada, and are essential to the health of Vancouver’s cultural community. That said, this type of conditional flexibility remains the exception.

Over the last five years, constellations of art spaces have been increasingly and rapidly coming to light in Vancouver neighbourhoods, but they often fade away just as quickly. In part, their disappearance is due to restrictive funding requirements and an ever-shrinking pot of funds that makes it extremely difficult for new spaces to achieve sustainability. In a number of cases, though, these new spaces were only ever meant to be temporary, remaining open only so long as their contextual possibilities also remained “open” Something that can both be and not be is said to be contingent; in a city with a vacancy rate hovering around one percent, independent spaces often exist simply as the result of some enthusiasm and just a little bit of available square footage. The fact that the resulting spaces can be or not be means that they perpetually embody potentiality, which is a stimulating proposition.

The Apartment is an art gallery run by Lee Plested and Erik yon Muller in their suite in Vancouver’s Parkview Towers, an iconic building near the mouth of False Creek. Approaching from the West End, this apartment building seems to rise up out of the trees as you reach the crest of the Burrard Street Bridge. In 1956, real estate developer (and future Vancouver mayor) Tom “Terrific” Campbell had to pull some serious strings to get the special rezoning required to build this modernist 14-storey “Y”-shaped building in a largely residential neighbourhood. At the time there was a significant public outcry against building the futuristic-looking Towers in such an incongruous setting. However, while this triskelion anomaly still fits in more with the nearby H.R. MacMillan planetarium than with any other domestic spaces in the surrounding area, the 53-year-old building is gaining public appreciation. Perhaps enough of Vancouver’s once ubiquitous modernist buildings have been destroyed that the remaining ones are finally becoming valued, or perhaps it’s just nostalgia for a past vision of a utopian future.

Contextualized within this distinct modernist building, and set against a sort of bucolic landscape, Plested and von Muller’s gallery space feels entirely autonomous from the surrounding residential neighbourhood and yet is rooted specifically within the domestic sphere. When visiting The Apartment, it’s all about “the apartment,” both as a type and as a home particular to Plested and von Muller. As an art space, The Apartment is purposefully segmented into distinct and yet interrelated galleries, each imbued with the specificities of their general domestic use. The bedroom houses contemporary art exhibitions, the living room usually contains “historical” works, and the bathroom often functions as a project space. The rest of the suite features works from Plested and von Muller’s collection, including a presentation of thrift store ceramics. When showing artworks in the bedroom, the bed is folded away and the room becomes a white cube, albeit one with a closet and thin white curtains on the windows that allow the space to be flooded with soft light.

At the time of my visit, on display was

Steven Shearer’s Uncle Jack, Mom & Steve, an exhibition specifically created for The Apartment. Shearer’s work often draws from and incorporates images from youth culture, but for this exhibition the artist presented his own work alongside artworks created by family members. As a youth, Shearer had observed these works in familiar domestic spaces: in his mother’s dressing room and in his uncle’s apartment. According to Plested, Shearer brought an etching by his mother and a painting by his uncle into his studio about a year and a half ago, where they entered into a dialogue with his own work. This exhibition presents a reunion of sorts within the domestic sphere of The Apartment.

In the living room gallery was a series of instruction pieces by Lee Lozano created between 1968 and 1972, many of which were pinned to a brown wall. As Plested explained, “We painted the room the colour of burlap in homage to Alfred Barr’s original MOMA, to question that very tenet of whether the exhibition of art is contingent upon the spaces it is exhibited in, and just to problematize it with its actual history because the original white cube was actually burlap.”

The exhibition of

beautiful paintings, which were not made public when they were produced, and which mark a move by the artist towards a dematerialized art practice and away from the art world, complicates conceptions of history in relation to artistic legacy.

That these works were displayed on the MOMAesque burlap paint job emphasizes the social and market conditions that originally led Lozano to abandon the art world, and which were also responsible for the success of her work posthumously-an irony further complicated by the fact that The Apartment is a commercial gallery.

Here we have a perpetuation of the historicization and institutionalization of conceptual artworks that at their point of production strove to be as anti-institutional as possible, coupled with an acknowledgement that this containment of resistance within art institutions is now seen to be all but inevitable. This reinforces the spirit of The Apartment as a space that acknowledges its complicity within the mechanisms of the art world, while positioning itself in a non-institutional environment. It is a particularized space, and a contextualized space, with some of the benefits of an institution.

I’m not sure if Plested and von Muller’s decision to sell art came before or after the decision to curate exhibitions in their apartment, but it certainly was given the same level of consideration as every other aesthetic or contextual decision. While this decision could be seen as a given, or perhaps as an inevitability, I prefer to view it as the strongest of many intelligent choices made by Plested and von Muller. Mechanisms of value always weigh heavily (though often invisibly) in spheres of display, and domestic spaces are no exception. Even discussions over dinner are reified. Capitalism is able to survive through the consumption and production of all social space; in The Apartment we are reminded of our susceptibility to these illusions.

But there is also a pragmatic side to maintaining a commercial practice: it means that The Apartment can offer artists and artworks more support and freedom than they might receive otherwise. While there are numerous frames of reference within The Apartment, there is also a lot of openness and possibility. Plested and Von Muller obviously care a great deal about art and they situate works very carefully. As Plested notes, “We have seen over the last 10 years [that] visual arts discourse has been completely co-opted by the economic structures of the market, and if there is a political and social use-value to art, it has not been the primary value over the last few years … we privilege ideas over value.”

For the visitor to this domestic commercial gallery, the benefits are clearly articulated in the way works that have been held over from previous exhibitions are displayed. I have always felt uncomfortable when venturing into customer lounges or open storage areas at commercial galleries. Such spaces seem haphazard, or in limbo; perhaps it’s because of the gallery’s need to keep artworks around, or to give them a context outside of the white cube so that collectors can imagine the art in their homes, but these works are often half-displayed, the only curatorial consideration being that they are by artists represented by the gallery. In The Apartment, the placement of these works is always extremely considered, partly because they intersect with the residents’ lifeworlds. Plested and Von Muller are selling used art.

The Apartment is situated on the southwest curve of the Parkview Towers, where two of the building’s wings intersect. The wall with windows is also concave, and the constantly changing light coming into the space almost seems to push the wall inward with it. It is impossible to forget the exterior of the building while inside it. Visitors entering the suite from the dark radial hallways are struck immediately by the light, which seems to follow them throughout their stay. The act of viewing artworks here reveals its contingent nature through the most basic of elemental changes: those of weather and light. Glancing out the window, visitors can see a large concrete sundial sculpture in the courtyard, which ostensibly proposes an interconnectivity between nature and culture but which, at the same time, reveals what Bruno Latour cites as the chief oddity of the moderns: “the idea of a time that passes irreversibly and annuls the entire past in its wake.”

During the initial planning stages for the spectacles that will surround the 2010 Olympic Winter Games in Vancouver, some cultural organizers suggested that the central point of focus be the False Creek Inlet near Science World. There was even talk of creating a giant fountain that would pump water from the creek into the air, but this idea was quickly shelved when it was noted that the industrial pollutants that had settled onto the bed of the inlet might cause a public heath hazard: exposure to too much history.

When Carpenter, da Conceicao, and Middleton opened the Bodgers’ and Kludgers’ Co-operative Art Parlour in August 2006, there was already another domestically grounded project happening in a backyard across the alley from their house. When the late-19th-century home where artist Kara Uzelman was living was slated for demolition, she began treating the place as a “site of interest” and started excavating her own backyard. Having studied dig procedures for six months with archeologist Ross Jamieson, Uzelman used scientifically accurate methodologies and techniques, while still incorporating a healthy dose of improvisation. Many of the tools she used were made from things she already had around the house; for instance, a hockey stick and a lamp pole were painted in precisely measured black and white stripes to indicate scale.

Following the provenance of her imagination, Uzelman began re-investing value in the things she uncovered by sculpting and organizing them. The first time I came across her project was when she held a garage sale in her backyard in order to find new homes for these “lost commodities,” some of which had been buried for decades. Many of the objects that didn’t sell were taken back into the house (from which they had likely come many years before), and became materials for Uzelman’s future sculptures. The artist also studied the ancient art of dowsing. I had always thought it was strictly a way of searching for water, but Uzelman assured me that it could be used to seek out objects as well. Still, when she and friend Erica Stocking first unearthed, and then began to reconstruct what they believed to be an ancient stone hot tub, I was sure that the relationship between dowsing and water had had something to do with it.

The tendency towards “making do” with the materials available has long been present in Strathcona, both within local art practices and simply as a means of survival for the members of the community. In the late 70s, local resident and artist Carole Itter, who creates sculptures from found materials, collaborated with another Strathcona resident, writer Daphne Marlatt, to collect and record local stories for an edition of Sound Heritage, a series of publications of recorded aural history that the province of British Columbia was producing at the time. Marlatt and Itter’s 1979 publication was called Opening Doors: Vancouver’s East End, and it included narrative accounts from nearly 60 local residents. In her introduction, Itter notes:

This was no utopia, this was the original

core of Vancouver’s East End … And at times

in the 1920s and 1930s many families were

raised and educated on the profits of home

scale bootlegging of wine and liquor, and

madams and prostitutes knew their business.

There was no money. There were pockets

of wealth. There were and still are backyard

vegetable gardens feeding households for

most months of each year.

The Bodgers’ and Kludgers’ Co-operative Art Parlour is an example of how neighbourhoods like Strathcona reveal that the distinctions we make between the public and private spheres are hazy at best. In contemporary households, a parlour usually just becomes an extra living room (or, at least in Vancouver, an extra bedroom), but its original intent was to be a place to receive guests, an interstitial space between the exterior facade and the internal realms of deep domesticity. For the most part, BKCAP was metonymically linked to the neighbourhood as a whole. The building housing it had itself long been a space of intersection between domesticity and commerce in the Strathcona area, as the main floor was the local sausage shop for many years. However, with the exception of opening nights, BKCAP was open by appointment only, or whenever a sandwich board was placed outside. Sometimes the frequency of its appearance was simply a reflection of how busy (or not busy) the housemates were. In any case, artists and curators responded enthusiastically to their approach and created projects for the Parlour that engaged with both the context of a living space and with the concerns and interests of the community where it was located.

In the early morning of August 25, 2006, siren sounds and plumes of smoke filled the air in Strathcona. The next day, yellow tape surrounded the blackened European Import warehouse on the western periphery of the neighbourhood. It appeared to have been ignited by the same mysterious arsonist who had targeted four nearby uninhabited homes in recent weeks. Local residents were on edge and soon began nightly patrols of the area. Strathcona has long been a space of particular cultural segmentation periodically marked by racialized tension and even violence, and yet at the same time had, as Daphne Marlatt notes, “a neighbourliness that transcended ethnic groupings and language barriers.” While speculation about motives ran rampant, the arsonist became the fantasy Other for the entire community. I don’t think the arsonist was ever caught, but as suddenly as the fires started happening, they stopped.

A year later, Kara Uzelman collaborated with Curtis Grahauer, then-artist-in-residence at The Bodgers’ and Kludgers’ Co-operative Art Parlour, to create an exhibition for the Parlour called Firewatcher. Inspired by the protectionism and paranoia that the arsons evoked, Grahauer and Uzelman developed the character of “Firewatcher” through a narrative installation that included a medieval turret made of handcrafted papercrete bricks, chainmail armour made from beer-can tabs, and a video presenting the neighbourhood through the fantasy framework of a Hitchcockian binocular view. And this was only the first materialization. Like much of Uzelman’s work, the Firewatcher project is continually being re-imagined and re-constructed. It has shown in different manifestations, including as part of exhibitions in Berlin and Toronto. Within these distant contexts, Strathcona becomes an imaginary space, prone to its own contingencies. At a distance, this neighbourhood becomes what Miwon Kwon calls an “[i]ntertextually coordinated, multiply located discursive field of operation,” a mode of experience, it should be noted, in which this very text is complicit.

But, much in the same way a fire quickly obliterates seemingly permanent structures, after hosting the two exhibitions that followed Firewatcher, The Bodgers’ and Kludgers’ Cooperative Art Parlour itself became dematerialized. After a year of hosting various projects, the space was getting a lot of attention, and its operation was subsequently becoming less and less a leisure activity for the proprietors. As Middleton conveyed to me, “It’s remarkable how fast a place can become an institution.”

The exhibition of beautiful paintings, which were not made public when they were produced, and which mark a move by the artist towards a dematerialized art practice and away from the art world, complicates conceptions of history in relation to artistic legacy.

That these works were displayed on the MOMAesque burlap paint job emphasizes the social and market conditions that originally led Lozano to abandon the art world, and which were also responsible for the success of her work posthumously-an irony further complicated by the fact that The Apartment is a commercial gallery.

Here we have a perpetuation of the historicization and institutionalization of conceptual artworks that at their point of production strove to be as anti-institutional as possible, coupled with an acknowledgement that this containment of resistance within art institutions is now seen to be all but inevitable. This reinforces the spirit of The Apartment as a space that acknowledges its complicity within the mechanisms of the art world, while positioning itself in a non-institutional environment. It is a particularized space, and a contextualized space, with some of the benefits of an institution.

I’m not sure if Plested and von Muller’s decision to sell art came before or after the decision to curate exhibitions in their apartment, but it certainly was given the same level of consideration as every other aesthetic or contextual decision. While this decision could be seen as a given, or perhaps as an inevitability, I prefer to view it as the strongest of many intelligent choices made by Plested and von Muller. Mechanisms of value always weigh heavily (though often invisibly) in spheres of display, and domestic spaces are no exception. Even discussions over dinner are reified. Capitalism is able to survive through the consumption and production of all social space; in The Apartment we are reminded of our susceptibility to these illusions.

But there is also a pragmatic side to maintaining a commercial practice: it means that The Apartment can offer artists and artworks more support and freedom than they might receive otherwise. While there are numerous frames of reference within The Apartment, there is also a lot of openness and possibility. Plested and Von Muller obviously care a great deal about art and they situate works very carefully. As Plested notes, “We have seen over the last 10 years [that] visual arts discourse has been completely co-opted by the economic structures of the market, and if there is a political and social use-value to art, it has not been the primary value over the last few years … we privilege ideas over value.”

For the visitor to this domestic commercial gallery, the benefits are clearly articulated in the way works that have been held over from previous exhibitions are displayed. I have always felt uncomfortable when venturing into customer lounges or open storage areas at commercial galleries. Such spaces seem haphazard, or in limbo; perhaps it’s because of the gallery’s need to keep artworks around, or to give them a context outside of the white cube so that collectors can imagine the art in their homes, but these works are often half-displayed, the only curatorial consideration being that they are by artists represented by the gallery. In The Apartment, the placement of these works is always extremely considered, partly because they intersect with the residents’ lifeworlds. Plested and Von Muller are selling used art.

The Apartment is situated on the southwest curve of the Parkview Towers, where two of the building’s wings intersect. The wall with windows is also concave, and the constantly changing light coming into the space almost seems to push the wall inward with it. It is impossible to forget the exterior of the building while inside it. Visitors entering the suite from the dark radial hallways are struck immediately by the light, which seems to follow them throughout their stay. The act of viewing artworks here reveals its contingent nature through the most basic of elemental changes: those of weather and light. Glancing out the window, visitors can see a large concrete sundial sculpture in the courtyard, which ostensibly proposes an interconnectivity between nature and culture but which, at the same time, reveals what Bruno Latour cites as the chief oddity of the moderns: “the idea of a time that passes irreversibly and annuls the entire past in its wake.”

During the initial planning stages for the spectacles that will surround the 2010 Olympic Winter Games in Vancouver, some cultural organizers suggested that the central point of focus be the False Creek Inlet near Science World. There was even talk of creating a giant fountain that would pump water from the creek into the air, but this idea was quickly shelved when it was noted that the industrial pollutants that had settled onto the bed of the inlet might cause a public heath hazard: exposure to too much history.

When Carpenter, da Conceicao, and Middleton opened the Bodgers’ and Kludgers’ Co-operative Art Parlour in August 2006, there was already another domestically grounded project happening in a backyard across the alley from their house. When the late-19th-century home where artist Kara Uzelman was living was slated for demolition, she began treating the place as a “site of interest” and started excavating her own backyard. Having studied dig procedures for six months with archeologist Ross Jamieson, Uzelman used scientifically accurate methodologies and techniques, while still incorporating a healthy dose of improvisation. Many of the tools she used were made from things she already had around the house; for instance, a hockey stick and a lamp pole were painted in precisely measured black and white stripes to indicate scale.

Following the provenance of her imagination, Uzelman began re-investing value in the things she uncovered by sculpting and organizing them. The first time I came across her project was when she held a garage sale in her backyard in order to find new homes for these “lost commodities,” some of which had been buried for decades. Many of the objects that didn’t sell were taken back into the house (from which they had likely come many years before), and became materials for Uzelman’s future sculptures. The artist also studied the ancient art of dowsing. I had always thought it was strictly a way of searching for water, but Uzelman assured me that it could be used to seek out objects as well. Still, when she and friend Erica Stocking first unearthed, and then began to reconstruct what they believed to be an ancient stone hot tub, I was sure that the relationship between dowsing and water had had something to do with it.

The exhibition of beautiful paintings, which were not made public when they were produced, and which mark a move by the artist towards a dematerialized art practice and away from the art world, complicates conceptions of history in relation to artistic legacy.

That these works were displayed on the MOMAesque burlap paint job emphasizes the social and market conditions that originally led Lozano to abandon the art world, and which were also responsible for the success of her work posthumously-an irony further complicated by the fact that The Apartment is a commercial gallery.

Here we have a perpetuation of the historicization and institutionalization of conceptual artworks that at their point of production strove to be as anti-institutional as possible, coupled with an acknowledgement that this containment of resistance within art institutions is now seen to be all but inevitable. This reinforces the spirit of The Apartment as a space that acknowledges its complicity within the mechanisms of the art world, while positioning itself in a non-institutional environment. It is a particularized space, and a contextualized space, with some of the benefits of an institution.

I’m not sure if Plested and von Muller’s decision to sell art came before or after the decision to curate exhibitions in their apartment, but it certainly was given the same level of consideration as every other aesthetic or contextual decision. While this decision could be seen as a given, or perhaps as an inevitability, I prefer to view it as the strongest of many intelligent choices made by Plested and von Muller. Mechanisms of value always weigh heavily (though often invisibly) in spheres of display, and domestic spaces are no exception. Even discussions over dinner are reified. Capitalism is able to survive through the consumption and production of all social space; in The Apartment we are reminded of our susceptibility to these illusions.

But there is also a pragmatic side to maintaining a commercial practice: it means that The Apartment can offer artists and artworks more support and freedom than they might receive otherwise. While there are numerous frames of reference within The Apartment, there is also a lot of openness and possibility. Plested and Von Muller obviously care a great deal about art and they situate works very carefully. As Plested notes, “We have seen over the last 10 years [that] visual arts discourse has been completely co-opted by the economic structures of the market, and if there is a political and social use-value to art, it has not been the primary value over the last few years … we privilege ideas over value.”

For the visitor to this domestic commercial gallery, the benefits are clearly articulated in the way works that have been held over from previous exhibitions are displayed. I have always felt uncomfortable when venturing into customer lounges or open storage areas at commercial galleries. Such spaces seem haphazard, or in limbo; perhaps it’s because of the gallery’s need to keep artworks around, or to give them a context outside of the white cube so that collectors can imagine the art in their homes, but these works are often half-displayed, the only curatorial consideration being that they are by artists represented by the gallery. In The Apartment, the placement of these works is always extremely considered, partly because they intersect with the residents’ lifeworlds. Plested and Von Muller are selling used art.

The Apartment is situated on the southwest curve of the Parkview Towers, where two of the building’s wings intersect. The wall with windows is also concave, and the constantly changing light coming into the space almost seems to push the wall inward with it. It is impossible to forget the exterior of the building while inside it. Visitors entering the suite from the dark radial hallways are struck immediately by the light, which seems to follow them throughout their stay. The act of viewing artworks here reveals its contingent nature through the most basic of elemental changes: those of weather and light. Glancing out the window, visitors can see a large concrete sundial sculpture in the courtyard, which ostensibly proposes an interconnectivity between nature and culture but which, at the same time, reveals what Bruno Latour cites as the chief oddity of the moderns: “the idea of a time that passes irreversibly and annuls the entire past in its wake.”

During the initial planning stages for the spectacles that will surround the 2010 Olympic Winter Games in Vancouver, some cultural organizers suggested that the central point of focus be the False Creek Inlet near Science World. There was even talk of creating a giant fountain that would pump water from the creek into the air, but this idea was quickly shelved when it was noted that the industrial pollutants that had settled onto the bed of the inlet might cause a public heath hazard: exposure to too much history.

When Carpenter, da Conceicao, and Middleton opened the Bodgers’ and Kludgers’ Co-operative Art Parlour in August 2006, there was already another domestically grounded project happening in a backyard across the alley from their house. When the late-19th-century home where artist Kara Uzelman was living was slated for demolition, she began treating the place as a “site of interest” and started excavating her own backyard. Having studied dig procedures for six months with archeologist Ross Jamieson, Uzelman used scientifically accurate methodologies and techniques, while still incorporating a healthy dose of improvisation. Many of the tools she used were made from things she already had around the house; for instance, a hockey stick and a lamp pole were painted in precisely measured black and white stripes to indicate scale.

Following the provenance of her imagination, Uzelman began re-investing value in the things she uncovered by sculpting and organizing them. The first time I came across her project was when she held a garage sale in her backyard in order to find new homes for these “lost commodities,” some of which had been buried for decades. Many of the objects that didn’t sell were taken back into the house (from which they had likely come many years before), and became materials for Uzelman’s future sculptures. The artist also studied the ancient art of dowsing. I had always thought it was strictly a way of searching for water, but Uzelman assured me that it could be used to seek out objects as well. Still, when she and friend Erica Stocking first unearthed, and then began to reconstruct what they believed to be an ancient stone hot tub, I was sure that the relationship between dowsing and water had had something to do with it.

The tendency towards “making do” with the materials available has long been present in Strathcona, both within local art practices and simply as a means of survival for the members of the community. In the late 70s, local resident and artist Carole Itter, who creates sculptures from found materials, collaborated with another Strathcona resident, writer Daphne Marlatt, to collect and record local stories for an edition of Sound Heritage, a series of publications of recorded aural history that the province of British Columbia was producing at the time. Marlatt and Itter’s 1979 publication was called Opening Doors: Vancouver’s East End, and it included narrative accounts from nearly 60 local residents. In her introduction, Itter notes:

This was no utopia, this was the original

core of Vancouver’s East End … And at times

in the 1920s and 1930s many families were

raised and educated on the profits of home

scale bootlegging of wine and liquor, and

madams and prostitutes knew their business.

There was no money. There were pockets

of wealth. There were and still are backyard

vegetable gardens feeding households for

most months of each year.

The Bodgers’ and Kludgers’ Co-operative Art Parlour is an example of how neighbourhoods like Strathcona reveal that the distinctions we make between the public and private spheres are hazy at best. In contemporary households, a parlour usually just becomes an extra living room (or, at least in Vancouver, an extra bedroom), but its original intent was to be a place to receive guests, an interstitial space between the exterior facade and the internal realms of deep domesticity. For the most part, BKCAP was metonymically linked to the neighbourhood as a whole. The building housing it had itself long been a space of intersection between domesticity and commerce in the Strathcona area, as the main floor was the local sausage shop for many years. However, with the exception of opening nights, BKCAP was open by appointment only, or whenever a sandwich board was placed outside. Sometimes the frequency of its appearance was simply a reflection of how busy (or not busy) the housemates were. In any case, artists and curators responded enthusiastically to their approach and created projects for the Parlour that engaged with both the context of a living space and with the concerns and interests of the community where it was located.

In the early morning of August 25, 2006, siren sounds and plumes of smoke filled the air in Strathcona. The next day, yellow tape surrounded the blackened European Import warehouse on the western periphery of the neighbourhood. It appeared to have been ignited by the same mysterious arsonist who had targeted four nearby uninhabited homes in recent weeks. Local residents were on edge and soon began nightly patrols of the area. Strathcona has long been a space of particular cultural segmentation periodically marked by racialized tension and even violence, and yet at the same time had, as Daphne Marlatt notes, “a neighbourliness that transcended ethnic groupings and language barriers.” While speculation about motives ran rampant, the arsonist became the fantasy Other for the entire community. I don’t think the arsonist was ever caught, but as suddenly as the fires started happening, they stopped.

The tendency towards “making do” with the materials available has long been present in Strathcona, both within local art practices and simply as a means of survival for the members of the community. In the late 70s, local resident and artist Carole Itter, who creates sculptures from found materials, collaborated with another Strathcona resident, writer Daphne Marlatt, to collect and record local stories for an edition of Sound Heritage, a series of publications of recorded aural history that the province of British Columbia was producing at the time. Marlatt and Itter’s 1979 publication was called Opening Doors: Vancouver’s East End, and it included narrative accounts from nearly 60 local residents. In her introduction, Itter notes:

This was no utopia, this was the original

core of Vancouver’s East End … And at times

in the 1920s and 1930s many families were

raised and educated on the profits of home

scale bootlegging of wine and liquor, and

madams and prostitutes knew their business.

There was no money. There were pockets

of wealth. There were and still are backyard

vegetable gardens feeding households for

most months of each year.

The Bodgers’ and Kludgers’ Co-operative Art Parlour is an example of how neighbourhoods like Strathcona reveal that the distinctions we make between the public and private spheres are hazy at best. In contemporary households, a parlour usually just becomes an extra living room (or, at least in Vancouver, an extra bedroom), but its original intent was to be a place to receive guests, an interstitial space between the exterior facade and the internal realms of deep domesticity. For the most part, BKCAP was metonymically linked to the neighbourhood as a whole. The building housing it had itself long been a space of intersection between domesticity and commerce in the Strathcona area, as the main floor was the local sausage shop for many years. However, with the exception of opening nights, BKCAP was open by appointment only, or whenever a sandwich board was placed outside. Sometimes the frequency of its appearance was simply a reflection of how busy (or not busy) the housemates were. In any case, artists and curators responded enthusiastically to their approach and created projects for the Parlour that engaged with both the context of a living space and with the concerns and interests of the community where it was located.

In the early morning of August 25, 2006, siren sounds and plumes of smoke filled the air in Strathcona. The next day, yellow tape surrounded the blackened European Import warehouse on the western periphery of the neighbourhood. It appeared to have been ignited by the same mysterious arsonist who had targeted four nearby uninhabited homes in recent weeks. Local residents were on edge and soon began nightly patrols of the area. Strathcona has long been a space of particular cultural segmentation periodically marked by racialized tension and even violence, and yet at the same time had, as Daphne Marlatt notes, “a neighbourliness that transcended ethnic groupings and language barriers.” While speculation about motives ran rampant, the arsonist became the fantasy Other for the entire community. I don’t think the arsonist was ever caught, but as suddenly as the fires started happening, they stopped.

A year later, Kara Uzelman collaborated with Curtis Grahauer, then-artist-in-residence at The Bodgers’ and Kludgers’ Co-operative Art Parlour, to create an exhibition for the Parlour called Firewatcher. Inspired by the protectionism and paranoia that the arsons evoked, Grahauer and Uzelman developed the character of “Firewatcher” through a narrative installation that included a medieval turret made of handcrafted papercrete bricks, chainmail armour made from beer-can tabs, and a video presenting the neighbourhood through the fantasy framework of a Hitchcockian binocular view. And this was only the first materialization. Like much of Uzelman’s work, the Firewatcher project is continually being re-imagined and re-constructed. It has shown in different manifestations, including as part of exhibitions in Berlin and Toronto. Within these distant contexts, Strathcona becomes an imaginary space, prone to its own contingencies. At a distance, this neighbourhood becomes what Miwon Kwon calls an “[i]ntertextually coordinated, multiply located discursive field of operation,” a mode of experience, it should be noted, in which this very text is complicit.

But, much in the same way a fire quickly obliterates seemingly permanent structures, after hosting the two exhibitions that followed Firewatcher, The Bodgers’ and Kludgers’ Cooperative Art Parlour itself became dematerialized. After a year of hosting various projects, the space was getting a lot of attention, and its operation was subsequently becoming less and less a leisure activity for the proprietors. As Middleton conveyed to me, “It’s remarkable how fast a place can become an institution.”

A year later, Kara Uzelman collaborated with Curtis Grahauer, then-artist-in-residence at The Bodgers’ and Kludgers’ Co-operative Art Parlour, to create an exhibition for the Parlour called Firewatcher. Inspired by the protectionism and paranoia that the arsons evoked, Grahauer and Uzelman developed the character of “Firewatcher” through a narrative installation that included a medieval turret made of handcrafted papercrete bricks, chainmail armour made from beer-can tabs, and a video presenting the neighbourhood through the fantasy framework of a Hitchcockian binocular view. And this was only the first materialization. Like much of Uzelman’s work, the Firewatcher project is continually being re-imagined and re-constructed. It has shown in different manifestations, including as part of exhibitions in Berlin and Toronto. Within these distant contexts, Strathcona becomes an imaginary space, prone to its own contingencies. At a distance, this neighbourhood becomes what Miwon Kwon calls an “[i]ntertextually coordinated, multiply located discursive field of operation,” a mode of experience, it should be noted, in which this very text is complicit.

But, much in the same way a fire quickly obliterates seemingly permanent structures, after hosting the two exhibitions that followed Firewatcher, The Bodgers’ and Kludgers’ Cooperative Art Parlour itself became dematerialized. After a year of hosting various projects, the space was getting a lot of attention, and its operation was subsequently becoming less and less a leisure activity for the proprietors. As Middleton conveyed to me, “It’s remarkable how fast a place can become an institution.”