The past is always inseparable from the present

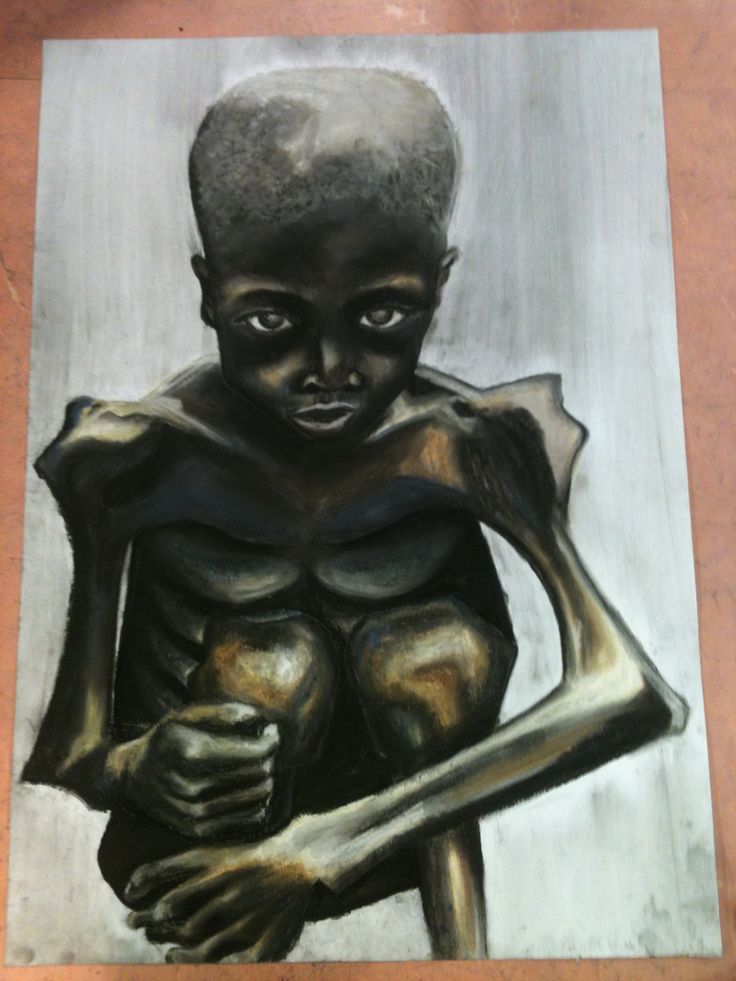

The past is always inseparable from the present. Its dialogue is a circuitous exchange. The present moment is one in which continued forms of colonialism are reared in every national institution–education, labour, health, trade and agriculture. In the time we spent together, Allen never missed an opportunity to connect the production of these cloths to a global awareness of transnational corporations, tariffs and the IMF–an awareness that further reflects on the historical weight of western media representing Africa as a totality of poverty, AIDS, war and starvation.

The exhibition also featured ready-to-wear, tailored pieces. The most striking example of this was the already mentioned men’s jacket with the image of Mobutu. “An unnerving aspect of any survey of African printed cloth,” Allen notes, “is the number of unsavoury characters on display. Idi Amin and Mobutu Sese Seko, among others, practiced a kind of politics that was corrupt and murderous.” To this, Allen asks a difficult but important question that makes me pause and remember the 90s, Malcolm and my Kente T-shirt. Why would anybody wear clothing celebrating them?

But this jacket is a worthy archive. It is an intricate piece inspired by one of the largest sporting events Africa the world has known. The 5 am fight in Zaire’s national stadium–incidentally above the prisons and persecutions dens–between George Foreman and Muhammad All is but one small, if important component of this jacket. Simply, I was taken aback and a little awed by this piece, and found myself somewhat sympathetic to the romanticism that it provokes. And not only does this jacket commemorate the authoritarian Mobutu as a difficult African nationalist and looming figure in wider Pan-African discussions, it attempts to recast him as an African statesman to many diasporic communities. But it also tells another story about consumer cultures, their consumption practices, and most interestingly, about global style.

At the heart of this art may very well be a sense of its kinesis and impulse to move ideas across time and space. None of these textiles, fabrics, banners or tailored pieces constrict their meanings within fortified frontiers of the nation. Yes, this is not to deny the specificity of the rich textile traditions in Mali, Ghana, Nigeria and Kenya, to only name some. Yet the underlying concern of the exhibition, in addition to showcasing the brilliancy of African textiles, is the question about the ways art must move and take on its own travel as the lifeblood of its maintenance. Whether it was the complex family planning banner or the tailored men’s jacket, this showing of African art is constituted by its restlessness and subversion of discrete histories.

These pieces constitute a political language fused into an emergent global fashion since European design houses started noticing African textiles–around the same time they started giving up the colonies and Africans seized independence. There is a glorious story of terror and emancipation that is sewn into these cloths that quite frankly demands our attention. This is global fashion and style against the backdrop of world politics. Why else, if I may aggravate those who wear branded Third-World heroes on their shirts, will socially conscious post-Seattle and post-Naomi Klein global youth wear Che Guevara on all their everyday wear?

Funny that. But, one would hope that in this after-moment, where political thought is jaded just about everywhere, that the entrails of a radical project are still interested in articulating a social justice platform. Something has got to linger. The moment we are in seems to involve picking up the pieces of so many fallen projects. And if you are wearing and reading the signs of the artist’s effort to communicate the history, politics and futures of hope, these textiles make a crucial offering.

Indigenous thought coalesces with modernizing forms in terse ways to produce clothes and clothing as the signposts of contemporary politics. African textiles are refined political languages for dealing with systems of kinship, identity and societal affiliations through sustained artistic representations. This is art’s critical tradition, in which the artist is at the heart of the exploratory, explanatory and emancipatory project.

It means that traditions of black expressive arts from Africa to the Americas emerge from within this legacy. How then to explain the transnational thrust–something the critical tradition of black arts has always been–of these textiles? (I’ve left my questions for the end.) What would wearing tailored pieces commemorating a figure of African independence (ponder that one) mean to our overdeveloped Western sense of self? How do these textiles and fabrics explore individual self-fashioning and collective bonding? Max Allen’s often astute and clear positions suggest that a more suspect understanding must go beyond the beauty and aesthetic value, and take seriously what we put on our backs.