It’s no secret that Vancouver artists enjoy special status in Europe. Recent programming at Rotterdam’s Witte de With provides evidence of this phenomenon. Sandwiched between last year’s

Brian Jungen exhibition and an upcoming show of Ian Wallace’s work are simultaneous exhibitions by Geoffrey Farmer and Gareth Moore. While this year has been particularly good to Farmer, with a mid-career survey at Montreal’s Musee d’art contemporain and his inclusion in the Sydney Bienniale, this exhibition is still a remarkable achievement for the relatively young artist, whose profile in Europe may not be as established as some Canadians think. Moore, on the other hand, is still making a name for himself both in Canada and abroad, having spent the last two years as an international transient for Iris Uncertain Pilgrimage project (2006-07). Their alignment within this prestigious institution comes as no accident–both share an affinity for eccentric round and manipulated objects that sit precariously within the gallery space and which frequently shift contexts over extended periods of time. These two exhibitions gave me–also a Vancouverite travelling abroad–an opportunity to consider the two artists, whose individual contributions establish a dialectical tension, to the benefit of both.

Moore’s new works draw inspiration from Austrian naturalist Viktor Schauberger, whose chief contribution to science seems to be a patently unscientific study of water. Water figures throughout As a Boat: a 16mm film entitled We both step and do not step in the same rivers, with Heraclitean bench (2008) is projected against a wall, within an installation of thorny branches, while the adjacent room offers Dutch visitors a glass of British Columbia spring water drawn from a wooden keg in For a spring abrim with songs of love is constantly reborn (2008). Around the corner lies Into the Water (In his Leather Breeches) (2008), a pair of pants fashioned from fish leather, flattened as if drying out. Moore clearly has affinities with Schauberger’s methods of autodidactic study in the world (as opposed to the hermetic confines of the academy), his own commitment to education existing chiefly in relation to casually appointed mentors that the artist chances upon in his travels. Whereas earlier projects such as Uncertain Pilgrimage took form from fleeting encounters with peripheral sites–the result of a nomadic and elusive methodology–here, the artist isolates objects neatly and sparingly within the gallery.

If As a Boar feels less ambiguous than Moore’s earlier work, it might be due to its narrative thrust, anchored as it is within in a small, beautifully printed book made available to the viewer in a modest cardboard box in the middle of the gallery floor. The text compiles a few selections from Schauberger’s writings and places the exhibition in the context of Moore’s research and affinities with the historical figure. This is not only significant for reading Moore’s own artistic process as a kind of evolving apprenticeship, wherein the artist foregrounds his relationships with mentor figures, living and dead, it also helps to distinguish the works from those of Farmer, who offers no guiding historical figure or text to contextualize his output, which is always fragmented and elusive.

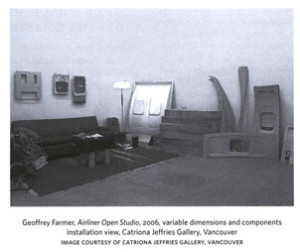

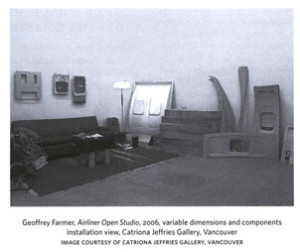

While Moore may have phantom-like tendencies, his presence located in the traces of his research, travels and sited relationships, Farmer is more like a poltergeist. Similarly hidden, yet indexed by the constant movement of things within the gallery, Farmer differs from Moore in that he cannot leave the gallery, as exhibitions dating back to Catriona Jeffries Catriona (2001) have made clear. Nocturnally haunting the gallery, disguised in a wig that deliberately aped the hairstyle of his dealer, Fariner continually altered not only his installations, but everything in the gallery down to the heating ducts and plumbing. In his first solo show at Witte de With, Farmer undertook a similar project, occupying the gallery at night and constantly shifting the installation that took his 2006 Vancouver exhibition Airliner Open Studio as its point of departure (this show, too, was predicated on the artist’s modus operandi of taking up residence in the gallery during the wee hours of the first month of its two-month run). Thus, the opening was really the beginning of the process, where viewers could reuse the same admission ticket until the show closed (allowing the viewer to re-enter an exhibition in a state of constant flux provides a nice institutional compliment to Farmer’s practice).

In contrast to the romantic, flowing narrative taking place one floor below, Farmer’s ongoing installation was marked with a sense of creeping discomfort. During my visit, in which I viewed just one iteration among dozens, I couldn’t help but feel as if I was trespassing upon something fraught and unresolved. Unlike the pre-emptive viewing of an unfinished painting or a rough draft of a piece of writing, here the combination of re-enactment–Airliner Open Studio revisited–and the artist’s compulsive refusal to complete the narrative made for a vexed yet exhilarating viewing experience. Like the first Airliner, the show incorporated a section of airline fuselage complete with cabin seating, which the artist slowly manipulated, transformed, decorated and dismantled over the duration of the show. Whereas the first airplane housing occupied the centre of Catriona Jeffries’ impressive project space, this time it took on a fragmented form. Instead of the massive, intact fuselage that was contextually bound to the Vancouver show, Farmer presented a partial section supplied by Aircraft-End-of-Life Solutions, a Dutch company that specializes in giving ancient airplanes a dignified retirement.

At the rime of my viewing (April 8 to be exact–each work in the show was labelled by date of alteration), the fuselage itself occupied just one quarter of the exhibit space, while familiar features such as its rowed seats were dispersed throughout the gallery. Also transformed is the overall labour process of the first exhibition, which fore-grounded the meticulous work required to clean the mould-infested airplane cabin, which had been rescued from a dilapidated farmhouse. Here, the process unfolds in a more diffuse and indirect manner, the airplane acting as a catalyst rather than the locus of meaning and activity.

Moore and Farmer’s offerings posited two very different conceptions of the artist’s role in the space of the museum-gallery. Not only different in form, the two shows also brought into focus two distinct notions of life and labour within an art practice. Farmer’s amateur/worker dialectic, a recurring theme, is exemplified in the artist’s emphasis on a constant, traumatic need to construct, transform and position generic objects. Unlike Moore’s recurring role of the apprentice, Farmer eschews any specific discipline of labour outside of the generic fact of work within the overarching context of

contemporary art and the specific location of the gallery (this brings to mind another recent work by the artist, occasioned by the MAC survey, which referenced Gordon Matta-Clark’s expression “not the work, the worker”). Moore’s role, by comparison all the more romantic, emerges in a dialectic of leisure and labour; the nomad who gleans for skills in the wide, open world.

Moore’s new works draw inspiration from Austrian naturalist Viktor Schauberger, whose chief contribution to science seems to be a patently unscientific study of water. Water figures throughout As a Boat: a 16mm film entitled We both step and do not step in the same rivers, with Heraclitean bench (2008) is projected against a wall, within an installation of thorny branches, while the adjacent room offers Dutch visitors a glass of British Columbia spring water drawn from a wooden keg in For a spring abrim with songs of love is constantly reborn (2008). Around the corner lies Into the Water (In his Leather Breeches) (2008), a pair of pants fashioned from fish leather, flattened as if drying out. Moore clearly has affinities with Schauberger’s methods of autodidactic study in the world (as opposed to the hermetic confines of the academy), his own commitment to education existing chiefly in relation to casually appointed mentors that the artist chances upon in his travels. Whereas earlier projects such as Uncertain Pilgrimage took form from fleeting encounters with peripheral sites–the result of a nomadic and elusive methodology–here, the artist isolates objects neatly and sparingly within the gallery.

If As a Boar feels less ambiguous than Moore’s earlier work, it might be due to its narrative thrust, anchored as it is within in a small, beautifully printed book made available to the viewer in a modest cardboard box in the middle of the gallery floor. The text compiles a few selections from Schauberger’s writings and places the exhibition in the context of Moore’s research and affinities with the historical figure. This is not only significant for reading Moore’s own artistic process as a kind of evolving apprenticeship, wherein the artist foregrounds his relationships with mentor figures, living and dead, it also helps to distinguish the works from those of Farmer, who offers no guiding historical figure or text to contextualize his output, which is always fragmented and elusive.

While Moore may have phantom-like tendencies, his presence located in the traces of his research, travels and sited relationships, Farmer is more like a poltergeist. Similarly hidden, yet indexed by the constant movement of things within the gallery, Farmer differs from Moore in that he cannot leave the gallery, as exhibitions dating back to Catriona Jeffries Catriona (2001) have made clear. Nocturnally haunting the gallery, disguised in a wig that deliberately aped the hairstyle of his dealer, Fariner continually altered not only his installations, but everything in the gallery down to the heating ducts and plumbing. In his first solo show at Witte de With, Farmer undertook a similar project, occupying the gallery at night and constantly shifting the installation that took his 2006 Vancouver exhibition Airliner Open Studio as its point of departure (this show, too, was predicated on the artist’s modus operandi of taking up residence in the gallery during the wee hours of the first month of its two-month run). Thus, the opening was really the beginning of the process, where viewers could reuse the same admission ticket until the show closed (allowing the viewer to re-enter an exhibition in a state of constant flux provides a nice institutional compliment to Farmer’s practice).

In contrast to the romantic, flowing narrative taking place one floor below, Farmer’s ongoing installation was marked with a sense of creeping discomfort. During my visit, in which I viewed just one iteration among dozens, I couldn’t help but feel as if I was trespassing upon something fraught and unresolved. Unlike the pre-emptive viewing of an unfinished painting or a rough draft of a piece of writing, here the combination of re-enactment–Airliner Open Studio revisited–and the artist’s compulsive refusal to complete the narrative made for a vexed yet exhilarating viewing experience. Like the first Airliner, the show incorporated a section of airline fuselage complete with cabin seating, which the artist slowly manipulated, transformed, decorated and dismantled over the duration of the show. Whereas the first airplane housing occupied the centre of Catriona Jeffries’ impressive project space, this time it took on a fragmented form. Instead of the massive, intact fuselage that was contextually bound to the Vancouver show, Farmer presented a partial section supplied by Aircraft-End-of-Life Solutions, a Dutch company that specializes in giving ancient airplanes a dignified retirement.

Moore’s new works draw inspiration from Austrian naturalist Viktor Schauberger, whose chief contribution to science seems to be a patently unscientific study of water. Water figures throughout As a Boat: a 16mm film entitled We both step and do not step in the same rivers, with Heraclitean bench (2008) is projected against a wall, within an installation of thorny branches, while the adjacent room offers Dutch visitors a glass of British Columbia spring water drawn from a wooden keg in For a spring abrim with songs of love is constantly reborn (2008). Around the corner lies Into the Water (In his Leather Breeches) (2008), a pair of pants fashioned from fish leather, flattened as if drying out. Moore clearly has affinities with Schauberger’s methods of autodidactic study in the world (as opposed to the hermetic confines of the academy), his own commitment to education existing chiefly in relation to casually appointed mentors that the artist chances upon in his travels. Whereas earlier projects such as Uncertain Pilgrimage took form from fleeting encounters with peripheral sites–the result of a nomadic and elusive methodology–here, the artist isolates objects neatly and sparingly within the gallery.

If As a Boar feels less ambiguous than Moore’s earlier work, it might be due to its narrative thrust, anchored as it is within in a small, beautifully printed book made available to the viewer in a modest cardboard box in the middle of the gallery floor. The text compiles a few selections from Schauberger’s writings and places the exhibition in the context of Moore’s research and affinities with the historical figure. This is not only significant for reading Moore’s own artistic process as a kind of evolving apprenticeship, wherein the artist foregrounds his relationships with mentor figures, living and dead, it also helps to distinguish the works from those of Farmer, who offers no guiding historical figure or text to contextualize his output, which is always fragmented and elusive.

While Moore may have phantom-like tendencies, his presence located in the traces of his research, travels and sited relationships, Farmer is more like a poltergeist. Similarly hidden, yet indexed by the constant movement of things within the gallery, Farmer differs from Moore in that he cannot leave the gallery, as exhibitions dating back to Catriona Jeffries Catriona (2001) have made clear. Nocturnally haunting the gallery, disguised in a wig that deliberately aped the hairstyle of his dealer, Fariner continually altered not only his installations, but everything in the gallery down to the heating ducts and plumbing. In his first solo show at Witte de With, Farmer undertook a similar project, occupying the gallery at night and constantly shifting the installation that took his 2006 Vancouver exhibition Airliner Open Studio as its point of departure (this show, too, was predicated on the artist’s modus operandi of taking up residence in the gallery during the wee hours of the first month of its two-month run). Thus, the opening was really the beginning of the process, where viewers could reuse the same admission ticket until the show closed (allowing the viewer to re-enter an exhibition in a state of constant flux provides a nice institutional compliment to Farmer’s practice).

In contrast to the romantic, flowing narrative taking place one floor below, Farmer’s ongoing installation was marked with a sense of creeping discomfort. During my visit, in which I viewed just one iteration among dozens, I couldn’t help but feel as if I was trespassing upon something fraught and unresolved. Unlike the pre-emptive viewing of an unfinished painting or a rough draft of a piece of writing, here the combination of re-enactment–Airliner Open Studio revisited–and the artist’s compulsive refusal to complete the narrative made for a vexed yet exhilarating viewing experience. Like the first Airliner, the show incorporated a section of airline fuselage complete with cabin seating, which the artist slowly manipulated, transformed, decorated and dismantled over the duration of the show. Whereas the first airplane housing occupied the centre of Catriona Jeffries’ impressive project space, this time it took on a fragmented form. Instead of the massive, intact fuselage that was contextually bound to the Vancouver show, Farmer presented a partial section supplied by Aircraft-End-of-Life Solutions, a Dutch company that specializes in giving ancient airplanes a dignified retirement.

At the rime of my viewing (April 8 to be exact–each work in the show was labelled by date of alteration), the fuselage itself occupied just one quarter of the exhibit space, while familiar features such as its rowed seats were dispersed throughout the gallery. Also transformed is the overall labour process of the first exhibition, which fore-grounded the meticulous work required to clean the mould-infested airplane cabin, which had been rescued from a dilapidated farmhouse. Here, the process unfolds in a more diffuse and indirect manner, the airplane acting as a catalyst rather than the locus of meaning and activity.

Moore and Farmer’s offerings posited two very different conceptions of the artist’s role in the space of the museum-gallery. Not only different in form, the two shows also brought into focus two distinct notions of life and labour within an art practice. Farmer’s amateur/worker dialectic, a recurring theme, is exemplified in the artist’s emphasis on a constant, traumatic need to construct, transform and position generic objects. Unlike Moore’s recurring role of the apprentice, Farmer eschews any specific discipline of labour outside of the generic fact of work within the overarching context of contemporary art and the specific location of the gallery (this brings to mind another recent work by the artist, occasioned by the MAC survey, which referenced Gordon Matta-Clark’s expression “not the work, the worker”). Moore’s role, by comparison all the more romantic, emerges in a dialectic of leisure and labour; the nomad who gleans for skills in the wide, open world.

At the rime of my viewing (April 8 to be exact–each work in the show was labelled by date of alteration), the fuselage itself occupied just one quarter of the exhibit space, while familiar features such as its rowed seats were dispersed throughout the gallery. Also transformed is the overall labour process of the first exhibition, which fore-grounded the meticulous work required to clean the mould-infested airplane cabin, which had been rescued from a dilapidated farmhouse. Here, the process unfolds in a more diffuse and indirect manner, the airplane acting as a catalyst rather than the locus of meaning and activity.

Moore and Farmer’s offerings posited two very different conceptions of the artist’s role in the space of the museum-gallery. Not only different in form, the two shows also brought into focus two distinct notions of life and labour within an art practice. Farmer’s amateur/worker dialectic, a recurring theme, is exemplified in the artist’s emphasis on a constant, traumatic need to construct, transform and position generic objects. Unlike Moore’s recurring role of the apprentice, Farmer eschews any specific discipline of labour outside of the generic fact of work within the overarching context of contemporary art and the specific location of the gallery (this brings to mind another recent work by the artist, occasioned by the MAC survey, which referenced Gordon Matta-Clark’s expression “not the work, the worker”). Moore’s role, by comparison all the more romantic, emerges in a dialectic of leisure and labour; the nomad who gleans for skills in the wide, open world.