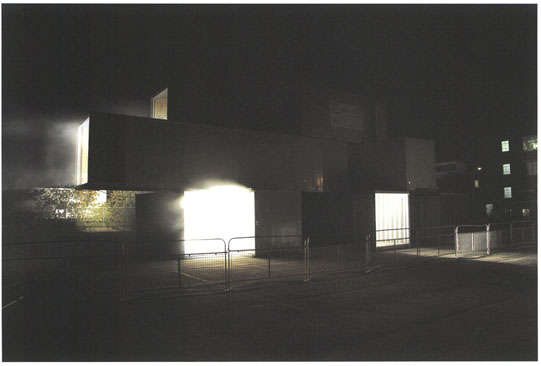

On October 4, 2008, the city of Toronto was energized by the arts for the third instalment of Nuit Blanche. This latest edition benefited from a geographical expansion, with new neighbourhoods such as Liberty Village included as sites of activity. In this location, curator Haema Sivanesan programmed seven installations that explored cultural diversity. Among them was Brendan Fernandes’ Future (… — — — …) Perfect, a large outdoor work made of stacked shipping containers.

Made of nine full-sized, industrial shipping containers stacked in a configuration that intentionally resembled Habitat ’67, the structure was impressive. Rising three storeys high, it took up an entire parking lot in Liberty Village. Each open container had six lights positioned inside, about eight feet back from the opening. The lights were programmed by Fernandes and a lighting designer to pulsate SOS in Morse code: three short flashes followed by three longer pulses followed by three short flashes. Set to a random sequence so that different containers lit up at different times, the calls for “help” took on the form of the container and were projected into the night.

Fernandes conceived the work to call attention to the notion of a modern-day dystopia. Habitat ’67 was built for the 1967 World’s Fair in Montreal; a model residential development intended to revolutionize housing for the masses. Today, elites inhabit the structure, which is surrounded by the decayed and abandoned Expo grounds. Future (… — — — …) Perfect was created in response and as a critique. Misinterpreted for its monumentality, Fernandes considered his project a “sad spectacle” because the work sent out a distress signal in a coded language that only few understand. The “sos” was meant as a warning about rapid urban development, gentrification and displacement of people which has affected Liberty Village as well as other communities in Toronto and in large urban centres across the world.

Because he divides his time between Toronto and New York, Fernandes’ art practice is defined by multimedia works that are politically driven, thought-provoking and always finely executed. In addition to Nuit Blanche, he has participated recently in exhibitions in China, Norway, South Africa, New York and Calgary, as well as the Dyed Roots exhibition at

desChamps Gallery. The following is an excerpt from our ongoing conversation about his developing practice.

CAROL-ANN M. RYAN What led you to develop the concept for your Nuit Blanche installation, Future (… — — — …) Perfect (FP)?

BRENDAN FERNANDES Ideas of migration and movement have always been part of my practice, due to my cultural trajectory and immigration to Canada from Kenya. Now that I’m living in Brooklyn, I see my neighbourhood changing from day to day. I’ve become more aware of cities and how people are being displaced–another form of migration–displacement through gentrification.

The concept for FP was inspired in part by this experience, but also by thinking about some of the largest cities in the world, new megacities, such as Shanghai, Beijing and Delhi, to name a few, that are taking over and consuming natural resources; big cities are “becoming”–moving people out to make way for new development. Even my home city of Toronto has become a “condoland.” FP as concept came out of these ideas and the deceptive notion that continued urban development will lead to a perfect future.

CR You have used themes of migration and gentrification in previous projects and I’m interested in how FP is situated within your practice up to this point. I’m thinking specifically of its temporary concept, as well as the notion of migration as represented by your use of cardboard boxes in prior works, and the notions of “home” and “becoming” that recur in recent projects. Do you see FP as a culmination of these ideas?

BF For sure. FP is the largest piece I have created so far and it was an opportunity to apply my ideas in an expansive form. In relation to previous works, FP is similar to Shelter Unit (2005) in its use of the mass-produced moving, or shipping, container. For the latter, I worked with cardboard boxes to build structure and landscape by piling them on top of each other. This choice was made to signify the box or container that one uses to move personal belongings. The box becomes a temporary home. With FP, I created a modular structure with shipping containers, which are larger forms of the box.

I’m thinking about ideas of changing urban cities and gentrification, but also about movement and, ultimately, change. The city is always changing and this influences identity, which I see as being in constant flux. It’s something that becomes new through experience. We’re experiencing progress and growth in our world cities, but now we face an economic crisis. The recent elections, both in Canada and the US, will affect us but we’re uncertain how and may feel unsettled as a result.

CR Was your working process affected by the knowledge that FP was temporary and would exist for only 12 hours?

BF The fact that Nuit Blanche is an art event that lasts for 12 hours was definitely something that I considered in my conceptual thinking of FP. I wanted the work to have a presence, but at the same time I used the temporality of the project to question its uncertainty. For me, the night of the event was part of its concept, but so was the building of it and even the morning after when the de-installation team began to tear it down almost immediately after Nuit Blanche ended.

For me, it was an “un-monumental” structure–almost pathetic in its calling for help–but, in its vulnerability, it created a mark of strength. The morning after, visiting the empty site, it was like nothing ever existed there. The structure was gone with no trace. That was a big part of what FP was about for me; it was erected for 12 hours and then it disappeared.

CR Can you talk a little about your participation in the Third Guangzhou Triennial in China, which was also a public art event, but much larger in scale and scope. Your work remained on display there for almost three months.

BF The theme of the Guangzhou Triennial was “Farewell to Post-Colonialism” so I knew the work of many artists who were involved.

The curators chose to show my video project Foe (2008), for which I hired an acting coach to teach me to speak in my cultural accents of Kenyan, Indian and Canadian. In the video, I read a passage from an art blog(

http://averageritual4791.webgarden.com), which is J.M. Coetzee’s sequel to Robinson Crusoe. A character named Friday (the savage) has been mutilated; his tongue has been removed and he cannot speak. I read the specific passage where Crusoe explains this to another. I am not interested in the authenticity of these accents as I speak, but in the idea of being taught to speak in these voices that “should” be natural for me.

CR As you acquire more experience pushing the boundaries of what your art and practice can be, along with your growing exposure, where do you go from here?

BF “Where do you go from here?” … Well, “go home.” I mean that literally. I am now interested in questioning my identity politic from a non-Western perspective. I want to test my work in the places that I am questioning. All of it has been created in the West and I want to take my work to the places that I am from. I want to go back to Kenya, for example, and question myself there; what have I become since leaving Kenya 20 years ago? I am not sure when this will happen, but I am beginning the process by relearning Swahili, a language in which I was once fluent but have forgotten since immigrating. I plan to use my Swahili to interview Kenyan mask-makers who produce objects for the souvenir industry in New York. I want to question how, by analogy, these “African” objects share a similar history with my identity(s) and the way that I function inside and outside my place(s) of origin.

The concept for FP was inspired in part by this experience, but also by thinking about some of the largest cities in the world, new megacities, such as Shanghai, Beijing and Delhi, to name a few, that are taking over and consuming natural resources; big cities are “becoming”–moving people out to make way for new development. Even my home city of Toronto has become a “condoland.” FP as concept came out of these ideas and the deceptive notion that continued urban development will lead to a perfect future.

CR You have used themes of migration and gentrification in previous projects and I’m interested in how FP is situated within your practice up to this point. I’m thinking specifically of its temporary concept, as well as the notion of migration as represented by your use of cardboard boxes in prior works, and the notions of “home” and “becoming” that recur in recent projects. Do you see FP as a culmination of these ideas?

BF For sure. FP is the largest piece I have created so far and it was an opportunity to apply my ideas in an expansive form. In relation to previous works, FP is similar to Shelter Unit (2005) in its use of the mass-produced moving, or shipping, container. For the latter, I worked with cardboard boxes to build structure and landscape by piling them on top of each other. This choice was made to signify the box or container that one uses to move personal belongings. The box becomes a temporary home. With FP, I created a modular structure with shipping containers, which are larger forms of the box.

I’m thinking about ideas of changing urban cities and gentrification, but also about movement and, ultimately, change. The city is always changing and this influences identity, which I see as being in constant flux. It’s something that becomes new through experience. We’re experiencing progress and growth in our world cities, but now we face an economic crisis. The recent elections, both in Canada and the US, will affect us but we’re uncertain how and may feel unsettled as a result.

CR Was your working process affected by the knowledge that FP was temporary and would exist for only 12 hours?

BF The fact that Nuit Blanche is an art event that lasts for 12 hours was definitely something that I considered in my conceptual thinking of FP. I wanted the work to have a presence, but at the same time I used the temporality of the project to question its uncertainty. For me, the night of the event was part of its concept, but so was the building of it and even the morning after when the de-installation team began to tear it down almost immediately after Nuit Blanche ended.

For me, it was an “un-monumental” structure–almost pathetic in its calling for help–but, in its vulnerability, it created a mark of strength. The morning after, visiting the empty site, it was like nothing ever existed there. The structure was gone with no trace. That was a big part of what FP was about for me; it was erected for 12 hours and then it disappeared.

CR Can you talk a little about your participation in the Third Guangzhou Triennial in China, which was also a public art event, but much larger in scale and scope. Your work remained on display there for almost three months.

BF The theme of the Guangzhou Triennial was “Farewell to Post-Colonialism” so I knew the work of many artists who were involved.

The curators chose to show my video project Foe (2008), for which I hired an acting coach to teach me to speak in my cultural accents of Kenyan, Indian and Canadian. In the video, I read a passage from an art blog(http://averageritual4791.webgarden.com), which is J.M. Coetzee’s sequel to Robinson Crusoe. A character named Friday (the savage) has been mutilated; his tongue has been removed and he cannot speak. I read the specific passage where Crusoe explains this to another. I am not interested in the authenticity of these accents as I speak, but in the idea of being taught to speak in these voices that “should” be natural for me.

The concept for FP was inspired in part by this experience, but also by thinking about some of the largest cities in the world, new megacities, such as Shanghai, Beijing and Delhi, to name a few, that are taking over and consuming natural resources; big cities are “becoming”–moving people out to make way for new development. Even my home city of Toronto has become a “condoland.” FP as concept came out of these ideas and the deceptive notion that continued urban development will lead to a perfect future.

CR You have used themes of migration and gentrification in previous projects and I’m interested in how FP is situated within your practice up to this point. I’m thinking specifically of its temporary concept, as well as the notion of migration as represented by your use of cardboard boxes in prior works, and the notions of “home” and “becoming” that recur in recent projects. Do you see FP as a culmination of these ideas?

BF For sure. FP is the largest piece I have created so far and it was an opportunity to apply my ideas in an expansive form. In relation to previous works, FP is similar to Shelter Unit (2005) in its use of the mass-produced moving, or shipping, container. For the latter, I worked with cardboard boxes to build structure and landscape by piling them on top of each other. This choice was made to signify the box or container that one uses to move personal belongings. The box becomes a temporary home. With FP, I created a modular structure with shipping containers, which are larger forms of the box.

I’m thinking about ideas of changing urban cities and gentrification, but also about movement and, ultimately, change. The city is always changing and this influences identity, which I see as being in constant flux. It’s something that becomes new through experience. We’re experiencing progress and growth in our world cities, but now we face an economic crisis. The recent elections, both in Canada and the US, will affect us but we’re uncertain how and may feel unsettled as a result.

CR Was your working process affected by the knowledge that FP was temporary and would exist for only 12 hours?

BF The fact that Nuit Blanche is an art event that lasts for 12 hours was definitely something that I considered in my conceptual thinking of FP. I wanted the work to have a presence, but at the same time I used the temporality of the project to question its uncertainty. For me, the night of the event was part of its concept, but so was the building of it and even the morning after when the de-installation team began to tear it down almost immediately after Nuit Blanche ended.

For me, it was an “un-monumental” structure–almost pathetic in its calling for help–but, in its vulnerability, it created a mark of strength. The morning after, visiting the empty site, it was like nothing ever existed there. The structure was gone with no trace. That was a big part of what FP was about for me; it was erected for 12 hours and then it disappeared.

CR Can you talk a little about your participation in the Third Guangzhou Triennial in China, which was also a public art event, but much larger in scale and scope. Your work remained on display there for almost three months.

BF The theme of the Guangzhou Triennial was “Farewell to Post-Colonialism” so I knew the work of many artists who were involved.

The curators chose to show my video project Foe (2008), for which I hired an acting coach to teach me to speak in my cultural accents of Kenyan, Indian and Canadian. In the video, I read a passage from an art blog(http://averageritual4791.webgarden.com), which is J.M. Coetzee’s sequel to Robinson Crusoe. A character named Friday (the savage) has been mutilated; his tongue has been removed and he cannot speak. I read the specific passage where Crusoe explains this to another. I am not interested in the authenticity of these accents as I speak, but in the idea of being taught to speak in these voices that “should” be natural for me.

CR As you acquire more experience pushing the boundaries of what your art and practice can be, along with your growing exposure, where do you go from here?

BF “Where do you go from here?” … Well, “go home.” I mean that literally. I am now interested in questioning my identity politic from a non-Western perspective. I want to test my work in the places that I am questioning. All of it has been created in the West and I want to take my work to the places that I am from. I want to go back to Kenya, for example, and question myself there; what have I become since leaving Kenya 20 years ago? I am not sure when this will happen, but I am beginning the process by relearning Swahili, a language in which I was once fluent but have forgotten since immigrating. I plan to use my Swahili to interview Kenyan mask-makers who produce objects for the souvenir industry in New York. I want to question how, by analogy, these “African” objects share a similar history with my identity(s) and the way that I function inside and outside my place(s) of origin.

CR As you acquire more experience pushing the boundaries of what your art and practice can be, along with your growing exposure, where do you go from here?

BF “Where do you go from here?” … Well, “go home.” I mean that literally. I am now interested in questioning my identity politic from a non-Western perspective. I want to test my work in the places that I am questioning. All of it has been created in the West and I want to take my work to the places that I am from. I want to go back to Kenya, for example, and question myself there; what have I become since leaving Kenya 20 years ago? I am not sure when this will happen, but I am beginning the process by relearning Swahili, a language in which I was once fluent but have forgotten since immigrating. I plan to use my Swahili to interview Kenyan mask-makers who produce objects for the souvenir industry in New York. I want to question how, by analogy, these “African” objects share a similar history with my identity(s) and the way that I function inside and outside my place(s) of origin.